Chapter Two: Marylands School Upoko Tuarua: Te Kura o Marylands

Whakatakinga

Introduction

1. To properly understand the pathways and circumstances that led to hundreds of boys entering into the care of the brothers of the Order, we must first look at the establishment of Marylands School, its functions, how it was funded and the role of the State.

2. Our findings about these matters are at the end of this chapter.

Te Whakatū i te Ratonga Karauna i te rohenga o ‘Oceania Province’ i te tau 1947

Establishment of the Order’s Oceania Province in 1947

3. The Oceania province of the Order was established in Australia in 1947 by two brothers from Ireland who arrived and set up a ministry. The following year, six more brothers arrived.

4. In 1950, the Order opened a school, Kendall Grange, for boys with learning difficulties in Morisset, New South Wales. In 1953, the brothers established another school at Cheltenham, Victoria, again for boys with learning disabilities.[56]

5. The Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse found that a weighted average of 40 per cent of members of the Brothers of St John of God within Australian institutions had allegations of child sexual abuse made against them from 1950 until 2010. [57]

Ka tae mai te Rangapū ki Aotearoa i te tau 1954, i runga i te pōhiri a ngā Pīhopa Katorika -te whakatūnga o te Kura o Marylands

Order comes to Aotearoa New Zealand in 1954 at invitation of Catholic bishops – establishment of Marylands School

6. The Order expanded from Australia to Aotearoa New Zealand in 1954 at the invitation of the New Zealand Catholic Bishops. The Archbishop of Auckland, James Liston, with support from the Bishop of Christchurch, suggested the Order take over a facility called Marylands in Middleton, Christchurch. At that time, Marylands was a home for ‘delinquent’ boys who were considered difficult or troublesome and was run by another Catholic Order, the Picpus Fathers.

7. In January 1955, the Bishop of Christchurch, Bishop Joyce advised the Picpus Fathers that Marylands would be closing, the reasons provided by the Bishop were that the “[i]ncreasing costs and a small number of boys have made this action necessary”.[58]

8. There are no records on what happened to the boys who had been residing at Marylands when the Picpus Fathers closed the home. The Order was notified in 2003 that an ex-Marylands student alleged that while he attended Marylands in the early 1950s (then run by the Picpus Fathers) he was sexually abused, and that he and two family members met with the Bishop of Christchurch about this (in around 1954).[59]

9. A letter from Bishop Joyce, to Archbishop Liston noted that the Order was interested in setting up a ministry in Aotearoa New Zealand.[60] The Order wanted to continue to work with disabled children, as it had been doing in both Australia and Ireland, and not with ‘delinquent’ or ‘difficult’ children. The Order’s intention was to open as a ‘foundation for retarded children’. At the time, the Order had run similar schools in Ireland and Australia, including the Order’s residential facility in Morisset, New South Wales.

10. The Order believed “delinquency [was] not its work, being nurses and psychiatrists, and not educators”. It was, however, “anxious to start a Foundation for retarded children, which … prevents later delinquency. [The Order’s] idea would be to take boys at 7 years of age, who would otherwise go to Mental Asylums, and by care and nursing, fit them for society”.[61]

11. In the months leading up to the opening of Marylands, Bishop Joyce endorsed the Order’s work and the Order spoke publicly about its expertise in similar work with children overseas.[62]

12. Under Canon Law, the Bishop of Christchurch had to give consent to the Order setting up a school for disabled boys in Christchurch, before the brothers could establish a facility there. The Order accepted Bishop Joyce’s official offer of the existing Marylands site in Christchurch in November 1954.

I whakawhirinaki atu te kura o Marylands ki te tahua pūtea a te Kāwanatanga hei kawe i ngā whakahaere

Order relied on State funding to operate Marylands School

13. The Order’s predominant focus when considering branching into Aotearoa New Zealand and opening Marylands School, was State funding.

14. When discussions between the Department of Health and the Order commenced, the focus of the discussions was on how much money both the Department of Health and the Department of Education was prepared to contribute, including for purchasing the Marylands property and the ongoing operational costs. We have been unable to find any evidence to suggest the State investigated whether the Order should be allowed to come to Aotearoa New Zealand to run this sort of institution or whether the brothers had suitable training and expertise to run Marylands School.

15. The Order initially planned to run Marylands with funding and support from the Department of Health, as it had done in Australia. This was consistent with the brothers’ perception of themselves as ‘nurses and psychiatrists, and not educators’.[63] However, Department of Health funding was available for only short-stay homes.[64] The Order had expected enthusiasm and government funding from the department’s Mental Hygiene Division and was disappointed when funding was unavailable.[65]

16. The Provincial requested that the Bishop of Christchurch write to the Prime Minister expressing his disappointment in the Department of Health. While the Bishop of Christchurch agreed, he instead wrote to the Minister of Health noting the Prime Minister’s support to the project. The Bishop requested a meeting between the Minister of Health and the Provincial to discuss this matter, on behalf of the Provincial.[66]

17. Brother Kilian reported to the Bishop that the Order was resistant to the involvement of the Department of Education:

“As you are aware the result of the recent visit to Wellington, in connection with the opening of Marylands, is most disappointing …

My opinion is that the Government are not anxious to alter the stupid legislation they have made in respect of short-stay homes. It would be against our principles to accept boys for two months only, as this is not the way to attack the big problem of mental deficiency, and they in Wellington are aware of this as well as I am. I feel we should not rush in to any acceptance of the paltry bait they are offering us …

Education means for us (Catholics) no progress in the mental deficiency field simply because most of the children will come from broken homes etc., and there will be little support from the families. Also Education offers us, perhaps a paltry grant towards capital costs and no per capita maintenance, which we are looking for. Also binding us down to the type of boy which in most cases are in my opinion ineducable.”[67]

18. Bishop Joyce wrote to the Minister of Health to request that the legislation be changed:

“May I respectfully point out that the Brothers’ work, which has a history of some 400 years, has always in every country throughout the world worked in conjunction with the Health authorities.

Would it be too much to suggest that the Act pertaining to short-stay homes be amended to include long-stay homes …”[68]

19. The Minister of Health at the time suggested the Order operate under the Department of Education instead, and open as a type of special school.[69] However, it was not long before it was agreed that Marylands would open as a “special school for retarded boys” under the Department of Health with, from the Order’s point of view, the Department of Education “having a slight interest in it”.[70] Private schools registered under the Education Act 1914 were to be inspected annually, however we have correspondence from the Order which suggests that Marylands and the Minister of Education agreed to an inspection once every two years and later, once every three years in accordance with the amendments to the education legislation in 1964.[71] The Department of Education was only able to locate records of two inspection reports for Marylands carried out by the Department of Education over the 29 years that Marylands was open.

Ngā paearu whakauru mō ngā ākonga ka kuraina ki te kura o Marylands

The enrolment criteria for students attending Marylands School

20. As Marylands was outside the State school system, students were not subject to the same admissions procedure for enrolment as the children who enrolled in State special schools for disabled children. Under the 1914 and 1964 legislation, the Director General could direct a child to be enrolled at a State special school or other State school if the parent was not able to carry out their primary duty to provide for their child’s education.[72]

21. Brother Kilian noted that “the powers that be in Wellington are arranging that the place be inspected and Licensed to be Special School”.[73] The Department of Education circular from 1955 compared pupils eligible for Marylands to pupils placed in special schools:

“The boys to be admitted fall into the same category as children admitted to special classes and schools for backward children. The range of mental ability at

Marylands will be the same as for special classes and schools except that special classes and schools take some children who are a little more able mentally than the

most able who will be admitted to Marylands.”[74]

22. A memorandum from the Minister of Health noted that children who were clearly incapable of being ‘trained’ to a level that might enable them to earn their own living would not be admitted.[75] This meant Marylands did not need to be licensed under the Mental Health Act (as originally anticipated), but rather registered under the Education Act 1914 as a Special School.[76] The Mental Hygiene Division was, however, interested in the work to be done at Marylands and would keep in touch with the brothers.[77]

23. Brother Kilian reported that:

“[t]he Minister mentioned that in order to make me happy about this arrangement I could call the place what I like and need never mention the word School as it was not expected that it would be conducted as a school but rather as a Training Centre for retarded boys.”[78]

24. The Order would consider the child’s suitability and then request the child to see a referring psychologist. This would be followed by a psychologist’s report, including “a Binet IQ range, comments on the boys’ behaviours during psychological examination, together with comments from teachers or any details of previous education which the child may have had”.[79]

Marylands accepted private referrals and State placements of boys from all parts of Aotearoa New Zealand, regardless of religious denomination.

25. It was expected that boys admitted to Marylands would have an IQ that fell within 50 to 70.[80] There were special circumstances that allowed for marginal cases of admission where a young person’s IQ fell between 40 and 50, such as a child with Down syndrome.[81]

Marautanga- Ko tā te Rangapū aronga ko te whakangungu, kaua ko te whāngai mātauranga

Curriculum – Order focused on training rather than education

26. Private schools had considerable flexibility to develop their curriculum and were not required to teach the State curriculum until private and religious schools were integrated into the State system following the passing of the Private Schools Conditional Integration Act 1975. However, a series of regulations were introduced from 1945 which required that every student, including in every private school, be given instruction in a list of subjects in accordance with a syllabus prescribed by the Minister. Despite this, the Inquiry has no evidence to suggest that these regulations were applied at Marylands, given the serious educational neglect of the students at Marylands. In addition to this, there was no specific curriculum for ‘backward’ children and special education teachers got very little help in adapting the curriculum for their pupils.[82]

27. The Order focused on training for low skilled occupations for the learning-disabled boys who lived at Marylands, rather than providing an education.

28. The basis of the registration of Marylands as a special school, and the whole basis for government approval for subsidy, was the Order’s agreement that they were not taking those who were ‘intellectually handicapped’, but rather those who had ‘mild subnormality’.[83] It was thought that children of this level had some prospect, even if it was a relatively small one, of eventually being able to earn their own living, and that was the object of the ‘training’.[84]

Te rēhita hei kura motuhake tūmataiti

Registration as a private special school

29. Prior to the Order opening Marylands, the Bishop of Christchurch vouched for the brothers as being suitably qualified to care and train the pupils - “The Brothers are specially trained for their work. The Brothers, who will conduct “Marylands” have their general and medical nursing diplomas, together with the Royal Medico – Physical Association’s Diploma in England for the care and training of intellectually handicapped children. Many of the Brothers become Doctors and Chemists.”[85]

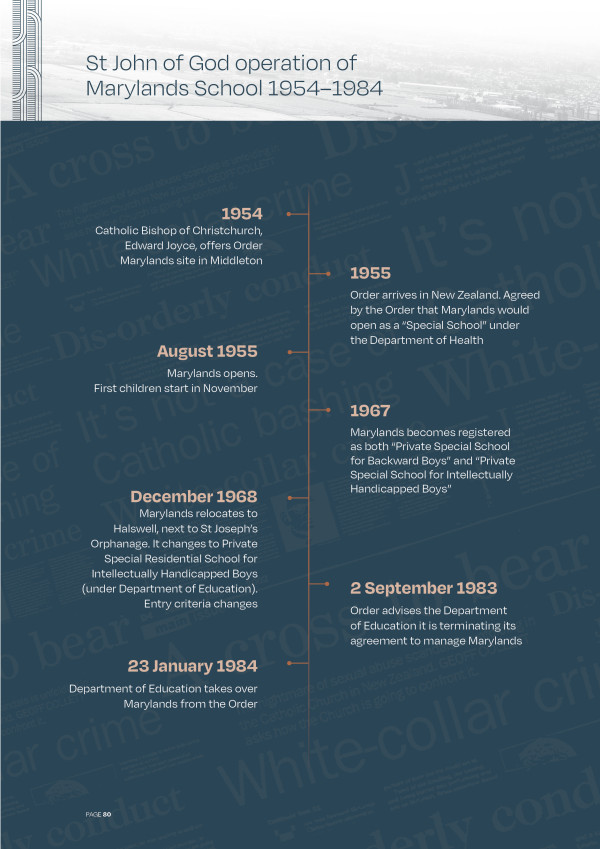

30. Marylands officially opened on 21 August 1955 to great fanfare,[86] but the first children did not start at the school until 14 November 1955 because funding issues remained unsettled.

31. Marylands was granted provisional registration as a private special school for ‘backwards boys’ on 11 November 1955. Full registration was confirmed on 7 December 1956, following an inspection of the school by the Department of Education.[87]

32. The Christchurch Senior Inspector of Schools reported favourably on the facilities and on the qualifications of the teachers. The inspector noted that the teachers were thoroughly practical and well-suited to “the teaching of the boys who will attend”,[88] despite being aware that the brothers were mostly health professionals, not educators.[89] The Inquiry saw no evidence to show on what basis the Christchurch Senior Inspector made this assessment.

33. The Order did not initially provide any specific training for residential care. The Order does not hold any formal policies or other documentation, on the training and education requirements of the brothers or any lay teachers or assistants at Marylands.[90]

Ka whāia e te Rangapū ngā moni āwhina i te tahua tautoko a te Kāwanatanga

Order seeks capital subsidy contributions from the State

34. The Order suggested to the Department of Health that parents should be charged £3 per week and if the parents could not pay, or could pay only a portion, the State should make up the difference.[91] The Order also sought a capital subsidy contribution from the State for the purchase price of the property from the Bishop of Christchurch and work required to prepare it to function as a school.

35. During this period of uncertainty, before students could be accepted into Marylands and funding negotiations were underway, members of the community sought updates from the Bishop of Christchurch regarding the delays in the opening of Marylands. In October 1955, the Bishop of Christchurch wrote to the Minister of Health, stating:

“I regret to state that during the past month, I have been attacked from all sides and from all sections of the community with the one question, when is Marylands going to open? Has anything gone wrong? I feel a cure, Honourable Sir, that between your good self and Brother Kilian some agreement can be reached which will allow the Brothers to commence their work immediately, and so keep faith with the public.”[92]

36. Following the meeting between the Provincial and the Minister of Health, Cabinet considered whether to provide funding to Marylands. On 22 November 1955, Cabinet agreed to Brother Kilian’s request for additional funds. Cabinet agreed to pay the Bishop of Christchurch “5 shillings per day, per bed”.[93] This was done through a letter from the Prime Minister to the Bishop of Christchurch, who accepted on behalf of the Provincial (in Australia).[94]

37. A decision about a capital subsidy was deferred.[95] The following year, the State approved a special grant to the Order to assist it in establishing Marylands.[96] In December 1957, the Order was transferred the property from the Bishop of Christchurch.[97]

38. Ngā momo ara i tae atu ngā tama ki te kura o Marylands

Different pathways of how boys arrived at Marylands School

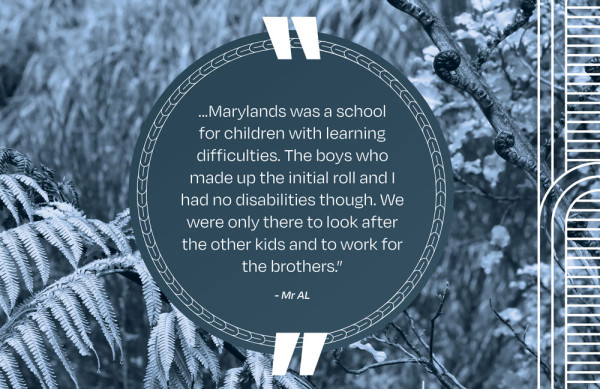

39. Despite the perception that Marylands School was to be a school for disabled boys, the reality was quite different. Of the first intake of 10 students to arrive at Marylands, six were transferred from the orphanage.[98] It appears that at least some of these students did not have disabilities.

40. The neighbouring property at Halswell was the orphanage, which was run by the Sisters of Nazareth. The two properties were separated only by a small river, the Heathcote River,[99] and a footbridge.

41. Mr AL was one of the six boys transferred from the orphanage to Marylands.[100] He told us that the initial intake was put to work to set up the school, rather than being in a classroom getting an education. They were involved in the day-to-day running of Marylands, from making the younger children’s beds, setting the table for disabled children and working in the garden and farmland surrounding Marylands.[101]

42. There is some evidence the brothers went to the orphanage for activities.[102] We heard evidence to suggest that the children at Marylands and the orphanage would often come together for sports days.[103] Some survivors recall being taken from the orphanage to Marylands to use the swimming pool,[104] for choir practice,[105] and, according to some survivors, for punishment and discipline by the brothers.[106] One Marylands survivor, Darryl Smith, recalls going over to the orphanage frequently and he also remembers the nuns relieving for the brothers at Marylands.[107]

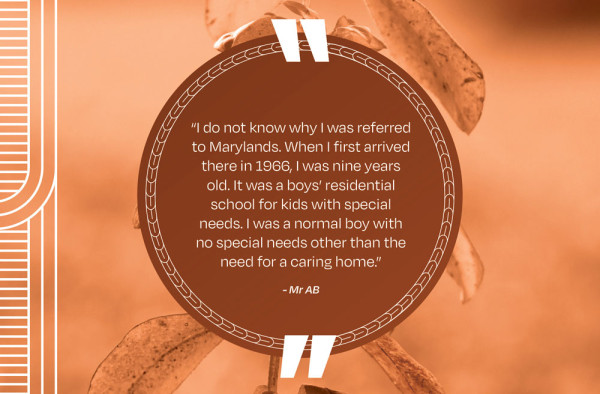

43. A large portion of those referred to Marylands were also State placements. The Department of Education placed boys recorded as having learning difficulties, those who struggled with reading and writing or could not keep up with the curriculum in State schools. Boys that were exhibiting difficult behaviour at home, trouble with police or a lack of anywhere else to go were also placed at Marylands. Many were not disabled.

“I do not know why I was referred to Marylands. When I first arrived there in 1966, I was nine years old. It was a boys’ residential school for kids with special needs. I was a normal boy with no special needs other than the need for a caring home.”[108]

44. Private placements were also arranged, and these were often influenced by the religious affiliation or religious adaption of a child’s family.

45. The Order has no records or information identifying children who attended Marylands School as Pacific or Māori, or those with disabilities.

Ngā whakaurutanga a te Kāwanatanga ki te kura o Marylands

State placements to Marylands School

46. The Department of Social Welfare or Psychological Services (a service of the Department of Education) placed and provided funding for many children and young people at Marylands.

47. State wards were children who had been removed from the care of their whānau for various reasons and placed in the care of the State.[109] The Department of Social Welfare fully subsidised the fees of State wards who were at Marylands.[110] From 1966, most referrals to Marylands were from Psychological Services.[111]

48. Prior Brother Boxall said in an October 1978 letter to the Department of Education:

“Marylands caters for boys who are specially recommended by the Psychological Services for residential care and education. A great percentage of these boys come because their needs cannot be adequately met in the usual day school situations owing to their gross social and/or emotional disturbances superimposed on their mild mental retardation. These pupils need a special environment, be it physical, psychological or social, necessary to fulfil their potential.”[112]

49. Of the 537 children and young people the Inquiry identified as having attended Marylands from 1955 to 1984, 152 had a Department of Social Welfare case file but not all of those had a status with the Department of Social Welfare during the period they were enrolled at Marylands.[113] During periods in the 1970s, about a quarter of the school’s roll were recorded as State wards.[114]

50. Survivors describe being sent to Marylands School because they came to the attention of social services due to their parents’ behaviours. Many describe trauma and abuse including sexual abuse and neglect in the family home. Some came from large families with single mothers who struggled to support their children.

51. Mr HZ from Ngāti Maniapoto and Ngāti Tūwharetoa, was a survivor from Marylands, Kimberley and Lake Alice child and adolescent unit. Mr HZ was placed in the care of the Department of Social Welfare at age three and said that he had “a long history of being taken into care by the State, released to my parents and then returned to care”.[115] On one occasion while in State care, Mr HZ saw his placement at Marylands as his only option:

“Upon my discharge from Palmerston North hospital for my ear operations, I was given two choices by the Department of Social Welfare. It was to go to Marylands or to go back to Lake Alice. Lake Alice had been so traumatising for me that I would do anything not to go back there.”[116]

52. The Department of Social Welfare had its own internal admission process. The guidelines for placement of State wards into a private boarding school would be approved if it were deemed to be “the most satisfactory placement for the ward”.[117] The Social Workers’ Manual required the child welfare officer to set out the reasons it would be in the child or young person’s best interests to be admitted to Marylands.[118]

53. Denis Smith, a former social worker with the Department of Social Welfare told the Inquiry that:

“There were wide variations in practice between individual social workers, offices, and institutions. There was no consistent national practice. The Manual was a guide. It was sometimes ignored or not followed if a social worker was not familiar with its contents. Different social workers could interpret the Manual differently. Often, social workers were unable to follow the Manual to the letter because of their workloads or other organisational constraints. Offices were often short-staffed, and at that time many of the staff had no professional social work qualifications.”[119]

Institutions were considered when the behaviour was considered beyond the ability of foster parents to handle, or when placement was for an older teenager. The resource issues, not the needs of the child, often dictated placement, and I believe this is still true today. I also believe that if I am right about this, then the ‘best interests of the child’ are simply not being served.”[120]

The whole placement environment involved searching around to see where there was a bed in a facility that took that age of child. Church-based institutions were another option – at times the only option.”[121]

54. Survivor Steven Long told us:

“I was admitted on my sixth birthday, and I was the youngest boy there. Child Welfare knew I was considerably younger than was usual for boys to be admitted to Marylands.”[122]

55. Peter Galvin, a general manager from Oranga Tamariki confirmed that the placement process was not a statutory requirement to consider and could give insight into how often the placement assessments on best interests were followed:

“It should be noted that these requirements were set out in practice guidance and social work manuals, rather than arising directly from statute or regulation.”[123]

Ngā whakaurutanga tūmatawhāiti ki te kura o Marylands

Private placements to Marylands School

56. Other referrals to Marylands were made privately and directly by families, by a general practitioner or psychologist, or with the encouragement of religious leaders and organisations such as Catholic Social Services and Presbyterian Social Services.[124]

57. In some cases, a motivating factor for placement at Marylands was their affiliation with the Catholic Church. Families believed their sons would receive an education best suited to their needs.[125] One survivor’s mother shared:

“Our family is Catholic so we thought it would be better than an IHC [Society for Intellectually Handicapped Children] school. Also, we thought that the brothers were doing it for the love of God.”[126]

58. One survivor, who came from an abusive home, was withdrawn at school and was regularly bullied. He attended a psychiatric assessment arranged by a nun working at his school. The psychiatrist suggested he “attend an all-boys’ school, to bring him out of his shell”.[127] He recalls his mother questioning the appropriateness of the placement at Marylands by the psychiatrist because he did not have any learning issues, but his father agreed because it was a Catholic school.

“My mother thought it was a bit strange because the boys at Marylands were all slow learners. She wasn’t happy about me going but, since it was only going to be for about two years, she agreed as well.”[128]

59. One survivor noted that their family experienced encouragement or pressure from the church to keep their children at Marylands, even when they had concerns. One family member of a survivor felt humiliated by the Bishop of Auckland, Archbishop Liston, and a parish priest in Auckland after trying to raise concerns about her son’s continued placement. Her daughter said:

“She spoke to Archbishop Liston and our parish priest after one of her visits to Marylands. She raised concerns she had for Marylands. They stated, ‘You don’t know how lucky you are, [Mrs DN], to have these brothers caring for your child’. I know my mother went away feeling humiliated when Archbishop Liston and the parish priest said that to her. It was easy to feel humiliated by these men back then. I always found it sickening when I was growing up. I often used to say to my mother, ‘They are only human; they can make mistakes’.

I know that she would not have taken it any further than that because you just did not question ‘authority’ like that back then.”[129]

Te ara i takahia ai e ngā tamariki hauā ki te kura o Marylands

Pathway of disabled children to Marylands School

60. Many of the boys who attended Marylands were placed there after having been actively excluded from their local schools or because their families had concluded the local school was not providing an appropriate service. There were limited other options in Christchurch, and even fewer options with the reputation that Marylands had established for itself.

61. Many families were not provided with support and instead were convinced to place their boys at Marylands. Mr IX told the Inquiry:

“There were no local schools that catered for students with intellectual disabilities, so I was sent to Marylands.”[130]

62. A previous caregiver at Marylands said the boys had “a wide range of difficulties, including epilepsy, Down syndrome, autism, dyslexia, Prader-Willi syndrome [or required] special care.”[131]

63. Some survivors told us at the time their need for extra support was not recognised by their schools prior to enrolment at Marylands and they later received a diagnosis of dyslexia or vision issues by psychiatrists.[132] Some were labelled ‘hyperactive’ and later diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

“I have dyslexia, and this was not identified in my earliest years at school. I was struggling at school and a local GP who was our family doctor, and whose name I don’t know, suggested to my parents enrol me at Marylands Residential School in Christchurch.”[133]

64. We heard from survivors who attended special classes at mainstream schools and were bullied due to the lack of integration and the way society perceived people with disabilities.

65. Mr CB described being bullied because of his disabilities. He disliked school and told us that he was constantly running away.

“I was bored because I couldn’t learn. I had some trouble with the other children, and I was picked on because of my disabilities.”[134]

66. Mr AB, told us that his vision impairment was undiagnosed as a child:

“I found out later in life, when I got glasses, that I had been vision impaired as a child. I had not recognised this as a child. I could not see what the teacher was writing on the blackboard. This may have been a contributing factor to me not wanting to go to school, and to my poor behaviour as a young child.”[135]

67. It is clear that children’s impairments went undiagnosed and mainstream schooling was usually not well-equipped to provide for the educational or wellbeing needs of disabled children.

68. Timothy Morgan was diagnosed as epileptic at the age of two. He suffered uncontrollable seizures in his teenage years, struggled academically and was placed at Marylands by his family.[136]

69. Some students at Marylands had physical disabilities.[137] There did not appear to be any requirement for social workers to assess the accessibility of the school grounds and facilities before placing State wards with physical disabilities.

Te ara i takahia ai e ngā tamariki Māori ki te kura o Marylands

Pathway of Māori children to Marylands School

70. We do not know the exact number of tamariki Māori who were at Marylands. The Order has no records or information identifying tamariki Māori who attended Marylands.

71. We do know that the number of tamariki Māori at Marylands was not as large as in Department of Social Welfare residences, especially during the 1970s and 1980s. It is likely, however, that of those placed at Marylands by the State, many were Māori.

72. We heard from Māori survivors who were sent to residences operated by the Department of Social Welfare before being moved to Marylands.

73. Adam Powell from Ngāti Raukawa and Tainui, was one of five children. Adam was adopted at an early age into a family with seven other children. He struggled academically, was partially deaf in one ear due to the physical abuse by his adoptive siblings, suffered respiratory problems and had a club foot until the age of six, when it was operated on. After the death of his adoptive mother, his adoptive family placed him at Marylands.[138]

74. James Tasker, a Māori survivor, told us he was from Ruatoria. James was referred to Marylands at age 14 after being expelled from several schools, which he says was due to his behaviour and being over the school age that Beck House Boys’ Home cared for.[139]

75. A Māori survivor, Trevor McDonald was sent to the orphanage in 1951 at age five and was moved to Marylands in November 1955. His mother was left to raise six children after his father was sent to prison.

“At the time I believe my father was in jail. There were six children in the family. My mother couldn’t cope with that number on her own.[140]

Te ara i takahia ai e ngā tāngata o Te Moana nui a Kiwa ki te kura o Marylands

Pathway of Pacific peoples to Marylands School

76. The Order has limited records or information identifying Pacific children who attended Marylands. The Inquiry acknowledges the lack of information about Pacific children enrolled at Marylands.

He nui rawa te utu mō ngā whakaurutanga tūmataiti ki te kura o Marylands

Private placements to Marylands School came at a significant cost

77. The Department of Social Welfare and the Department of Education funded the placements of children at Marylands.

78. However, for private placements, fees were not fully subsidised and the responsibility to pay these fell on the families that placed their children at Marylands. For some families these fees and associated attendance costs caused serious financial hardship.

79. Danny Akula told us he was withdrawn from Marylands because his mother “did not pay any maintenance for me the whole time I was there”. [141] One Māori survivor spent only one term at Marylands before being withdrawn by his grandparents, who could not afford the school fees.[142]

80. Ms DN, whose brother attended Marylands, talked about the financial impact:

“The school was not cheap, and it involved air flights each school holidays. Those days there were only three term breaks – in May, August and December (the Christmas holidays). Air travel was not as accessible as it is today and along with the expensive flights, I clearly remember having to prepare and pack for his return to school. It involved everything from school uniform, weekend wear, underwear, and toiletries (for example six cakes of soap,

six tubes of toothpaste etc.). The list was long and expensive.”[143]

I te tau 1968 i huri te kura o Marylands hei Kura Motuhake Tūmataiti Noho Tara-ā-Whare mō ngā tama hinengaro hauā -

In 1968 Marylands School became a Private Special Residential School for Intellectually Handicapped Boys

81. In December 1968 when Marylands relocated from Middleton to the larger site at 26 Nash Road, Halswell, Christchurch, the cohort of students also changed. The Order sought registration to take students with more serious learning difficulties. It applied to the Department of Education for the registration of a portion of Marylands as a “special school for the intellectually handicapped”.[144]

82. In June 1967, the Prior, Brother Kilian Herbert, advised the Department of Education that:

“The change in policy at Marylands is, that since we left our old premises at Halls Road, and moved to this larger place at Halswell Road, we have opened a special residential section for

the occupational-type boy. This is a small unit of twenty beds. I.Q. 30/50. On the same property, but some distance removed from the occupational centre, we have seventy boys in residential units. These are from 50/70 I.Q.”[145]

83. It was recommended that the number of ‘intellectually handicapped’ boys be limited to 20 because of the availability of suitable classroom accommodation and of the separate detached villa where these boys would be housed.[146]

84. From 1967, Marylands became registered as both a “Private Special Residential School for Backward Boys” and a “Private Special School for Intellectually Handicapped Boys”.[147] Pupils classified as ‘intellectually handicapped’ were eligible for a higher daily subsidy from the Department of Health of $1.20 per day (later $1.60 per day) compared with 50 cents per day for other pupils.[148]

85. The State paid a capital subsidy of $39,000 to set up accommodation for ‘intellectually handicapped’ children at Halswell.[149]

He aha i wehe ai te Rangapū i te kura o Marylands

Why the Order decided to withdraw from Marylands School

86. Funding continued to be a major issue with the Order seeking more resources from the State to run Marylands. The Ministers of Education and Health announced a special grant of $10,000 to help meet any deficit in Marylands’ operating costs during 1972 and a further grant of $20,000 for 1973.[150]

87. The Order also wanted the State to help fund new school buildings. On 13 February 1973, the Minister of Education and the Associate Minister of Finance inspected Marylands and promised publicly that the State would take immediate steps to rebuild Marylands’ buildings.[151]

88. The Minister of Education suggested the State should buy the land and school and be responsible for its maintenance and the rebuild.[152] The State would lease the school to the Order for a nominal rent and further discussions would take place about the State’s contribution towards the running expenses of the school.[153]

The Prior, Brother Rodger Moloney, accepted this offer in principle.[154]

89. In a 1973 report, Treasury observed that the only sensible approach was to rebuild the school.[155] However, the cost of rebuilding was around $15,000 per bed.[156] At the time, the maximum State assistance per bed for a home for intellectually handicapped children was $5,000.[157] The largest State subsidy available was for accommodation for older people at $7,200 for a home bed and $8,600 for a hospital bed.[158] Therefore, the Marylands cost was out of line with other assistance in the sector.[159]

90. A Cabinet memorandum dated 15 March 1973 observed that Marylands was already receiving State assistance through three State departments: Health, Social Welfare and Education.[160]

91. On 26 March 1973, Cabinet authorised the Department of Education to negotiate to purchase the land necessary for the school from the Order under the Public Works Act 1928.[161] One factor considered in making this decision, was that Marylands was catering for many boys who would otherwise be a direct responsibility of the State.[162]

92. However, the Order was dissatisfied with the Cabinet decision and lobbied for more support.[163] A new, more generous funding agreement was negotiated as a result.[164]

93. In addition, the Cabinet Committee on Social Affairs confirmed the policy of meeting Marylands’ operating losses until the school became established in the new buildings provided by the State.[165]

94. Stage one of the new buildings (residential accommodation for 90 boys) was completed in 1978.[166] The Order was reminded it would be responsible for the operating costs of the new complex once the school was fully established.[167] Brother Boxall “could not understand how his people could have entered into [that agreement]”.[168] He said annual deficits were running at around $100,000 and the Order would not be able to meet such a cost.[169]

95. Treasury expressed concern about the significant increase in the school’s operating deficit.[170] The Private Schools Integration Act 1975 gave private schools the opportunity to move into the State-run education system. This meant that they would obtain State funding to maintain and modernise buildings, on the basis that ownership of the land and buildings was retained by the proprietors. [171]

This remedy was not available to Marylands as the State had already paid for the site and buildings.[172]

96. In April 1981, the Order submitted a proposal to the Minister of Education that Marylands be granted special financial assistance in the future.[173] The Order said the operating costs of Marylands required more income than could be derived from fees, donations, and the normal grants and subsidies applying to private special schools and residential facilities for ‘handicapped’ children.[174] It sought an ongoing special grant.[175]

97. Between 1972 and 1982, the Department of Education paid the Order a total of $1,317,484 in special deficit grants.[176] On 28 June 1982, Cabinet approved the continued payment of annual grants to Marylands to reimburse operating losses, subject to certain conditions.[177]

98. On 2 September 1983, the Order advised the Department of Education it was terminating the agreement it had with the Department of Education to manage Marylands.[178]

99. The Order said that the department’s funding would never enable it to bring the children to their “full potential”, even with generous public support.[179] Therefore, the Order considered it better that Marylands become part of the State system.[180] A further reason for the decision was that the Order was short of brothers to run Marylands.[181]

100. Another factor, but not one expressed in official correspondence, was that the cohort of students they were dealing with had changed over time to include disabled boys who had higher support needs. Brother Coakley told us:

“[W]e had a lot of meetings with the government, that started in ‘81, ‘82 and then they wouldn’t increase the grant because we really needed more staff, for the type of kids because I actually expelled about three, four kids from there because some were very very aggressive and that can be very destructive for other kids and not so much in the school but all in the villas and that you see and all towards your co-workers. So things were certainly changing and so we decided ok we are virtually running a State school now and so we will let them go and so I remember announced to the staff that the Brothers will withdraw early 84.”[182]

101. Brother Garchow, who was acting for the Provincial at the time, wrote to Bishop Ashby (Bishop of Christchurch) to say the Order’s General Curia (the administrative headquarters) had requested confirmation that the Bishop of Christchurch had no objection to the Order withdrawing.[183] The Bishop of Christchurch replied to say, although he regretted the necessity of Marylands closing, he accepted it.[184]

Ka tīmata tā te Kāwanatanga whakahaere i te kura o Marylands

State takes over Marylands School

102. Department of Education officers visited Marylands on 13 September 1983 to carry out a preliminary assessment.[185] They concluded there was merit in making it a State-run special school.[186] The additional annual cost of doing so was assessed at $650,000. [187] The main reason for the increased cost was that the brothers, whom the Department of Education paid a stipend of $21,000 per year, would need to be replaced by salaried staff.[188]

103. In a September 1983 Cabinet memorandum, the Minister of Education proposed that Cabinet agree in principle to the acceptance of the control and administration of Marylands.[189] This proposal was approved by Cabinet on 19 September 1983, subject to conditions to be confirmed by the Cabinet Committee on Family and Social Affairs.[190] An official transfer date of 23 January 1984 was noted.[191] As part of this agreement, it was proposed to change the name of the school immediately to Hogben School.[192]

104. When the Department of Education took over the school in 1984, it found the school to be in poor shape. Many teachers employed by the Order to teach at Marylands lacked specialist qualifications and teaching experience.[193]

105. In the 1984 annual report on Marylands, the appointed principal of Hogben School said:

“Many pupils found the new management strategies strange initially. Their expectations were of physical chastisement …

It was quite obvious that in the laundry and to a lesser extent in the garden, boys had been used to supplement a shortfall in labour …

Most teachers inherited have poor qualifications and lack significant teaching experience. None had any specialist qualifications. As a result the quality of the teaching programme was not high, there was a lack of coordinated programmes, individual classes did their ‘own thing’, management techniques were lacking. There was, and still is with some, poor understanding of the boys’ ability. Too little was expected and there was a strong resistance to academic programming. Many boys seen only as workshop material and programmed accordingly. There was little understanding of boys needs in the outside world. Programmes of weaving, art work and ‘nimble fingers’ craft work that dominated did not prepare boys for living in the regular community.”[194]

106. Seven full-time teachers were transferred from Marylands.[195] The principal noted that there was a small number of teachers who continued to resist the new programmes and goal setting.[196] Classroom co-ordination, age banding, the removal of corporal punishment, the withdrawal of the right to religious teaching in the classroom, and the change in direction away from the intellectually handicapped had all been contentious issues.[197]

107. By the time of the 1985 annual report, matters had reportedly improved considerably. The principal noted that it was “particularly heartening to observe boys previously ‘written off’ to be reading and undertaking classroom activities previously regarded as beyond their possibilities.”[198]

108. Despite reports of improved student learning, in 1997 two reports of sexual abuse were alleged against two Hogben School nightshift attendants by several students.[199] Both nightshift attendants were charged, but only one was convicted.

109. It appears that many records were lost during the transition period. Some were apparently burned.[200]

Ngā Whakakitenga: Ngā ara ki te taurimatanga

Findings: Pathways into care

110. The Royal Commission finds at Marylands:

a. Tamariki were referred to Marylands by State agencies, health professionals and parents. It was established for disabled boys but many boys who attended were not disabled. Some of the boys were placed at Marylands as State wards, some had behavioural problems and were excluded from their local school, and some were placed at Marylands because their whānau were either advised or felt they would get a better education.

b. The psychological, learning and educational needs of tamariki placed at Marylands by the State, or privately, were often inadequately assessed at the time of placement. Their emotional and physical needs were not met nor was their need for a loving home.

c. Private placements to Marylands were charged attendance fees and other associated costs that placed significant strain on some whānau and prevented enrolment and attendance.

[56] Witness statement of Brother Timothy Graham, WITN0837001, para 35.

[57] Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, Analysis of claims of child sexual abuse made with respect to Catholic Church institutions in Australia, Sydney, June 2017, p 16 (Using a weighted average approach).

[58] Te Rōpū Tautoko Marylands Briefing Paper 7: Picpus Fathers and Marylands, as amended 24 September 2021, CTH0015324, p 4.

[59] Letter from J D Hall, Barrister and Solicitor to Lee Robinson of Saunders Robinson, regarding alleged abuse by client who attended Marylands School in 1950, CTH0014934_00018 (16 July 2003) p 1–2.

[60] Letter from the Bishop of Christchurch to the Archbishop, regarding the establishment and nature of care proposed by the St John of God Brothers, CTH0015246 (1954), p 6.

[61] Letter from the Bishop of Christchurch to Archbishop Liston, discussing the nature of care to be provided by the Order, CTH0015143_00005 (14 October 1954), p 6.

[62] Newspaper article, ‘Retardate Boys, Care By Brothers of St John of God, Provincials Address’, MOH0000945 (The Press, 9 June 1955), p 317.

[63] Letter from the Bishop of Christchurch to Archbishop Liston, discussing the nature of care to be provided by the Order, CTH0015143_00005 (14 October 1954), p 6.

[64] Mental Health Amendment Act 1954, section 3(2).

[65] Letter from Provincial Brother Kilian to the Bishop of Christchurch Edward Joyce, regarding discussions around initial State funding, CTH0015145 (19 February 1955), p 5.

[66] Letter from Brother Kilian to Bishop Joyce, regarding State involvement in the opening of Marylands School, CTH0015141 (12 September 1955), p 1.

[67] Letter from Brother Kilian to Bishop Joyce, update on legislation to include long-stay care home, CTH0015141 (1 October 1955), p 5.

[68] Letter from the Bishop of Christchurch to the Minister of Health, requesting amendments to legislation to include long-stay care homes and a personal interview between the Minister of Health and the Provincial of the Order, CTH0015141 (24 October 1955), p 12–13.

[69] Letter from Brother Kilian to the Bishop of Christchurch, regarding Marylands opening under the Department of Health and discussions on capital expenditure, CTH0015141 (2 November 1955), p 14–15.

[70] Letter from Brother Kilian to the Bishop of Christchurch, CTH0015141, p 14–15.

[71] Letter from Brother Kilian to the Bishop of Christchurch, CTH0015141, p 14–15.

[72] See also: Brief of evidence of Helen Hurst for the Ministry of Education, WITN0099003 (Royal Commission, 7 October 2021), para 4.6.

[73] Letter from Brother Kilian to the Bishop of Christchurch, CTH0015141, p 15.

[74] Circular sent by Mr AB Allen, Senior Psychologist of the Department of Education, outline of the admission testing criteria, interpretation of I.Q ranges, and I.Q. range for admission to Marylands, CTH0015141 (6 December 1955), p 3.

[75] Memorandum from the Minister of Health to Cabinet, Brothers of St John of God “Marylands” Home for Mentally Retarded Boys, Halls Road, Middleton, Christchurch, MOE0002070 (18 November 1955), p 2.

[76] Memorandum from the Minister of Health to Cabinet, MOE0002070, p 2.

[77] Memorandum from the Minister of Health to Cabinet, MOE0002070, p 2.

[78] Letter from Brother Kilian to the Bishop of Christchurch, CTH0015141, pp 14.

[79] Letter from the Office for Special Education to Mr A Allen, Marylands – Christchurch, MOE0002076 (1 February 1956) p 1. See also: Department of Education circular, regarding the I.Q. range for admission to Marylands, CTH0015142 (6 December 1955), p 3.

[80] Letter from Brother Kilian to the Bishop of Christchurch, CTH0015141, p 14–15.

[81] Letter from the Officer for Special Education to Mr A Allen, Marylands – Christchurch, MOE0002076 (1 February 1956). See also: Department of Education circular, regarding the I.Q. range for admission to Marylands, CTH0015142 (6 December 1955), p 3.

[82] Glass, M, “Description and evaluation of special education for backward pupils at primary and intermediate schools in New Zealand” (1977), Massey University https://mro.massey.ac.nz/handle/10179/7839.

[83] Letter from the Officer for Special Education to Mr A Allen, MOE0002076.

[84] Letter from the Officer for Special Education to Mr A Allen, MOE0002076.

[85] Bundle of documents relating to the Order of St John of God, including memorandum to the Minister of Health, MOH0000945, p 315.

[86] Witness statement of Brother Timothy Graham, WITN0837001, para 71.

[87] Brief of evidence from Helen Hurst (Associate Deputy Secretary, Ministry of Education), EXT0020167, para 4.4.

[88] Letter from the Senior Inspector of Schools to the Department of Education, MOE0002064 (4 November 1955).

[89] Bundle of documents relating to the Order of St John of God, including memorandum to the Minister of Health, MOH0000945, p 315.

[90] Witness statement of Brother Timothy Graham, WITN0837001, paras 58–59.

[91] Letter from Brother Kilian to the Bishop of Christchurch, CTH0015141, p 14–15.

[92] Letter from the Bishop of Christchurch to the Minister of Health, CTH0015141, p 12–13.

[93] Letter from Prime Minister Holland to Bishop Joyce, regarding cabinet approved maintenance subsidy for Marylands students, CTH0015141 (22 November 1955), p 17.

[94] Letter from Bishop Joyce to Prime Minister Holland, accepting Cabinet’s subsidy payment, CTH0015141 (2 December 1955), p 18.

[95] Letter from Prime Minister Holland to Bishop Joyce, CTH0015141, p 17. On 22 November, the Prime Minister noted Cabinet had given preliminary consideration to providing a capital subsidy for the establishment of Marylands but the decision was deferred until further information could be obtained.

[96] Letter to the Director of Education from the Deputy Director-General of the Department of Health, regarding the approval of state funding to assist the Order of St John of God to purchase property, MOE0002079 (26 September 1956).

[97] Witness statement of Brother Timothy Graham, WITN0837001, para 74(c).

[98] Marylands Students Admissions Register, CTH0010185 (1955-1983), pp 1–2.

[99] Witness statement of Brother Timothy Graham, WITN0837001, para 84.

[100] Witness statement of Mr AL, WITN0623001, (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 7 May 2021), para 3.15.

[101] Witness statement of Mr AL, WITN0623001, paras 4.1–4.2.

[102] NOPS investigation report: allegation of physical and sexual abuse – Peter John Wall, (12 November 2018), CTH0012752, p 9.

[103] NOPS investigation report: allegation of physical and sexual abuse – Peter John Wall, (12 November 2018), CTH0012752, p. 9.

[104] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 253.

[105] A Private Session transcript, CRM0014147 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 5 August 2021), p 7.

[106] Witness statement of Mr IY, WITN1023001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 16 December 2021), para 4.11.

[107] Witness statement of Darryl Smith, WITN0840001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 13 September 2021), paras 52–53, 58.

[108] Witness statement of Mr AB, WITN0420001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 19 April 2021), para 35.

[109] Kerryn Pollock, ‘Children’s homes and fostering – Government institutions’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/childrens-homes-and-fostering/page-2 (accessed 1 April 2023).

[110] Letter from the Director of Mental Health to the Director-General of Education, regarding government subsidy payments for Marylands students, MOE0002131 (25 July 1972), p 1.

[111] Witness statement of Brother Timothy Graham, WITN0837001, para 105.

[112] Letter from Brother Boxall to the Department of Education, staff complement at Marylands, MOE0002341 (4 October 1978), p 1.

[113] Crown submissions regarding Marylands School response to notice to produce 310, CRL0250951 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 12 November 2021), p 3.

[114] Te Rōpū Tautoko Marylands Briefing paper 3: Marylands residential special school: contextual analysis, MSC0007270 (30 July 2021), para 22.

[115] Witness statement of Mr HZ, WITN0324015, (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 14 May 2021), para 9.

[116] Witness statement of Mr HZ, WITN0324015, para 26.

[117] Child Welfare Division of the Department of Education, Social Workers‘ Manual, ORT0000035 (1970–1984), p 250.

[118] Crown submissions regarding Marylands School response to notice to produce 310, CRL0250951, para 2.3.

[119] Witness statement of Denis Smith, WITN0184001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 15 December 2021), para 45.

[120] Witness statement of Denis Smith, WITN0184001, para 81.

[121] Witness statement of Denis Smith, WITN0184001, para 82.

[122] Witness statement of Steven Long, WITN0744001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 15 October 2021), para 23.

[123] Brief of evidence of Peter Galvin for Oranga Tamariki, WITN1056001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 4 February 2021), para 18.

[124] Marylands Students Admissions Register, CTH0010185, pp 1-2.

[125] Witness statement of Ms DN, WITN0870001, (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 30 September 2021), paras 2.28–2.29.

[126] Witness statement of Ms IO, WITN0558001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 10 January 2021), para 30.

[127] Witness statement of Mr IH, WITN0671001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 15 October 2020), para 23.

[128] Witness statement of Mr IH, WITN0671001, para 24.

[129] Witness statement of Ms DN, WITN0870001, paras 2.58–2.59.

[130] Witness statement of Mr IX WITN0889001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 24 November 2021), para 19.

[131] Witness statement of Ms AM, WITN0587001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 4 June 2020), para 2.3.

[132] Witness statement of Alan Nixon, WITN0716001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 8 October 2021), para 135.

[133] Witness statement of Mr CZ, WITN0535001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 19 May 2021), para 1.6.

[134] Witness statement of Mr CB, WITN0813001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 22 November 2021), para 2.6.

[135] Witness statement of Mr AB, WITN0420001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 19 April 2021), para 30.

[136] Witness Statement of Timothy Morgan, WITN0803001, (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 11 August 2021), paras 7, 16.

[137] Witness statement of Adam Powell, WITN0627001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 14 June 2021), para 3.

[138] Witness statement of Adam Powell, WITN0627001, para 17.

[139] Witness statement of James Tasker, WITN0675001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 5 July 2021), paras 13, 18.

[140] Witness statement of Trevor McDonald, WITN0399001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 22 April 2021), para 3.3.

[141] Witness statement of Danny Akula, WITN0745001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 13 October 2021), para 57.

[142] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 193.

[143] Witness statement of Ms DN, WITN0870001, para 2.62.

[144] Letter from Brother Kilian to the Regional Superintendent, Department of Education, MOE0002100 (22 April 1967).

[145] Letter from Brother Kilian Herbert to Senior Psychologist, Department of Education, regarding the policy change on I.Q. entry criteria to Marylands School, MOE0002104 (6 June 1967).

[146] Letter from DJ Callandar, Senior Adviser on Backward Pupils, Department of Education to the Psychological Services, MOE0002122 (6 October 1967).

[147] Letter from D.H. Ross, Director-General of Education to S.S.P. Hamilton, Regional Superintendent of Education, notifying the granting of joint registration of Marylands School, MOE0002112 (24 August 1967).

[148] Letter from the District Senior Inspector of Schools, Office of the Senior Inspector of Schools to the Superintendent of Education, Department of Education, MOE0002106 (27 June 1967), p 1; Letter from D.H. Ross, Director-General of Education to S.S.P. Hamilton, Regional Superintendent of Education, providing an update on the registration of Marylands as a private special residential school for intellectually handicapped boys, MOE0002109 (22 August 1967); Ministry of Education submission in response to the Royal Commission of Inquiry’s (notice to produce 25), MOE0002536, p 54, referring to letter dated 25 July 1972 from the Department of Health to the Department of Education.

[149] Letter from the District Senior Inspector of Schools, to the Superintendent of Education, MOE0002106, p 1; Ministry of Education submission in response to the Royal Commission of Inquiry’s (notice to produce 25), MOE0002536, p 54, referring to letter dated 25 July 1972 from the Department of Health to the Department of Education.

[150] Memorandum for Cabinet Committee on Social Affairs, Ministry of Education, regarding Marylands’ operating costs and state funding, MOE0002214 (6 November 1972), p 1.

[151] Letter from the Minister of Education to the Minister of Finance, regarding the inspection of Marylands School on 13 February 1973, CTH0015153 (7 March 1973), p 1.

[152] Letter from the Minister of Education to Brother Moloney, regarding the purchase of land and buildings, CTH0015152 (17 February 1973), p 1.

[153] Letter from the Minister of Education to Brother Moloney, CTH0015152, p 1.

[154] Letter from Prior Brother Rodger Moloney to Mr P.A. Amos, Minister of Education, regarding the Order’s acceptance of a leasing arrangement of new school buildings, MOE0002195 (6 March 1973); Memorandum for Cabinet from the Minister of Education, MOE0002199, p 3.

[155] Letter from the Minister of Education to the Minister of Finance, regarding special grants, MOE0002196 (7 March 1973), p 5.

[156] Letter from the Minister of Education to the Minister of Finance, MOE0002196, p 4.

[157] Letter from the Minister of Education to the Minister of Finance, MOE0002196, p 4.

[158] Letter from the Minister of Education to the Minister of Finance, MOE0002196, p 4.

[159] Letter from the Minister of Education to the Minister of Finance, MOE0002196, p 4.

[160] Memorandum for Cabinet from the Minister of Education, requests made by the Order of St John of God for operating and reconstruction costs, MOE0002199, p 3.

[161] Letter from the Secretary of Cabinet to the Minister of Education, endorsing government assistance and authorising negotiations regarding land purchase, CTH0015155 (26 March 1973); Cabinet memorandum to Minister of Education, Cabinet meeting 26 March 1973, regarding financial assistance to Marylands Special School, MOE0002201 (27 March 1973).

[162] Memorandum for Cabinet, regarding Marylands School and the proposed financial assistance, CTH0015154 (15 March 1973), para 6.

[163] Memorandum to the Minister of Finance, regarding financial assistance to Marylands Special School, MOE0002243 (9 December 1974), pp 1–10.

[164] Memorandum to the Minister of Finance, MOE0002243, pp 1–10.

[165] Proposal to Minister of Education from Director General of Education, regarding proposed financial assistance for Marylands School, CTH0015156 (24 April 1979), p 1.

[166] Proposal to Minister of Education from Director General of Education, CTH0015156, p 1.

[167] Meeting notes from 28 April 1978 meeting at Marylands Special School, including Department of Education, MOE0002333 (8 May 1978), p 1.

[168] Meeting notes from 28 April 1978 meeting at Marylands Special School, MOE0002333 , p 1.

[169] Meeting notes from 28 April 1978 meeting at Marylands Special School, MOE0002333 , p 1.

[170] Letter from the Minister of Education to the Minister of Finance, regarding Marylands School Christchurch: Special Deficit Grants, MOE0002377 (13 November 1979), p 2.

[171] Ministry of Education submission in response to the Royal Commission of Inquiry’s Notice to Produce No. 202: Schedule 2, MOE0002844 (5 July 2021), p 32–33.

[172] Letter from M K Burns (Director-General) to the Minister of Education, regarding Marylands Special School, Christchurch, MOE0002407 (21 May 1980), p 1.

[173] Letter from Stephen Coakley (Prior/Administration) to the Minister of Education, rearding a proposal for special financial assistance for Marylands, MOE0002438 (6 May 1981), p 1.

[174] Letter from Stephen Coakley to the Minister of Education, MOE0002438, p 1.

[175] Letter from Stephen Coakley to the Minister of Education, MOE0002438, p 1.

[176] Ministry of Education submission in response to the Royal Commission of Inquiry’s Notice to Produce No. 202: Schedule 2, MOE0002844, p 32.

[177] Memorandum from Cabinet Secretary to Ministers, regarding Marylands Special School, MOE0002480 (June 1982).

[178] Letter from Brother Anthony Leahy to the Minister of Education, meeting confirmation to discuss the Order’s decision to terminate the agreement to run Marylands School, MOE0002488 (2 September 1983).

[179] Letter from Brother Anthony Leahy to the Minister of Education, MOE0002488.

[180] Letter from Brother Anthony Leahy to the Minister of Education, MOE0002488.

[181] Memorandum for Cabinet from Minister for Education, confirmation of the termination of the agreement to run Marylands School by the Order, MOE0002490 (15 September 1983), p 1.

[182] Transcript of evidence of Brother Stephen Coakley, MSC0008045 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 20 July 2021), p 12.

[183] Letter from Brother Raymond Garchow to Bishop Ashby, regarding the withdrawal of the Order from Marylands, CTH0016753 (20 January 1984).

[184] Letter from Bishop Ashby to Brother Anthony Leahy, regarding the closure of Marylands, regrets the necessity of Marylands closing but accepts its closure, CTH0016752 (24 January 1984).

[185] Memorandum for Cabinet from Minister for Education, regarding Marylands Special School, MOE0002490 (15 September 1983), p 2.

[186] Memorandum for Cabinet from Minister for Education, MOE0002490, p 2.

[187] Memorandum for Cabinet from Minister for Education, MOE0002490, p 2.

[188] Memorandum for Cabinet from Minister for Education, MOE0002490, p 2.

[189] Memorandum for Cabinet from Minister for Education, MOE0002490, p 2.

[190] Extract from Minutes of Cabinet Committee meeting held on 19 September 1983, regarding Marylands Special School, MOE0002492 (21 September 1983).

[191] Extract from Minutes of Cabinet Committee meeting held on 20 September 1983, regarding Marylands Special School, MOE0002495 (21 September 1983), p 2.

[192] Proposal from the Director-General, Department of Education to the Minister of Education, MOE0002531 (17 July 1984), p 1.

[193] 1984 Annual Report for Hogben School, by B D Bridges, Principal MOE0002851 (1984), p 9.

[194] 1984 Annual Report for Hogben School, MOE0002851, pp 2, 4 and 9.

[195] Ministry of Education submission in response to the Royal Commission of Inquiry’s Notice to Produce No. 202: Schedule 2, MOE0002844, p 8.

[196] 1984 Annual Report for Hogben School, MOE0002851, p 10.

[197] 1984 Annual Report for Hogben School, MOE0002851, p 10.

[198] 1985 Annual Report for Hogben School, by B D Bridges, Principal, MOE0002852 (1985), p 5.

[199] Witness Statement of Graeme Daniel, WITN1307001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 27 May 2021), para 32.

[200] NZ Police Report Form, Sergeant L F Corbett, files regarding complaints of sexual abuse against McGrath, NZP0014848 (29 October 1993), p 2.