Executive Summary Whakarāpopototanga ripoata

More than 40 years on, the recollections of survivors, ngā purapura ora, remain as vivid and raw as ever of their experiences of the Lake Alice Psychiatric Hospital.[1] This case study examines the torture, tūkino (abuse, harm and trauma) and neglect suffered by children and young people admitted, often for no good reason, to Lake Alice Psychiatric Hospital’s child and adolescent unit from 1972 to 1980.[2]

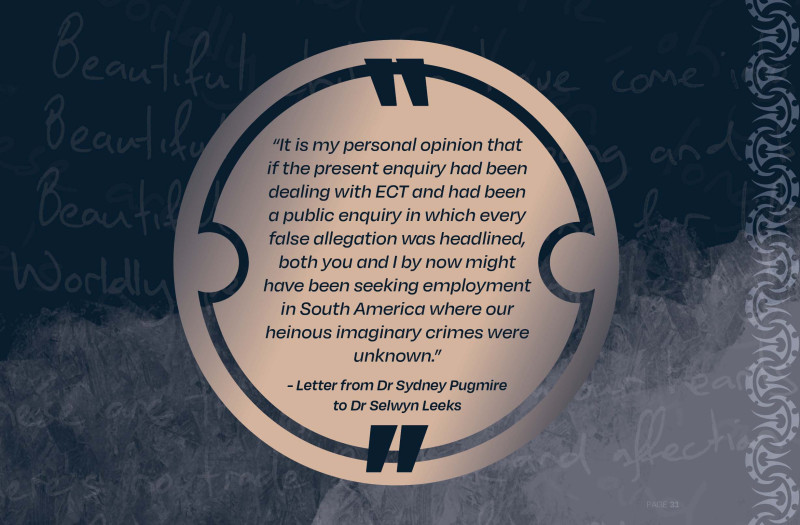

The unit was established in the Lake Alice hospital in Manawatū, which is in the rohe of Ngāti Apa and Ngā Wairiki. It was an institution, somewhat typical of its time, set up to treat children and young people with mental distress or mental illness. Instead, it became a place of abuse, particularly at the hands of its consultant psychiatrist, Dr Selwyn Leeks. Leeks’ conduct was abusive and unjustified by any standards, even those of the day. For many, Lake Alice was a place of misery, neglect, terror and torment.

The Departments of Health and Social Welfare supported the establishment of a unit, and the Department of Education supported the setting up of a school at Lake Alice. During this time, parents, whānau, communities, the public and even senior mental health professionals were conditioned to believe the assurances of Dr Leeks that those sent to the unit would receive beneficial psychiatric treatment.

Many of the children and young people at the unit came from disadvantaged or marginalised communities in Aotearoa New Zealand. Māori made up more than a third of those admitted to the unit. Most children and young people admitted to the unit came from social welfare care.

Incomplete records, misdiagnoses, racism, homophobia, transphobia and a failure to recognise what we now know to be neurodiversity mean we will never have a complete understanding of the demographics of those children and young people placed at the unit.

Many of the children and young people at Lake Alice grew up in disadvantaged households with limited access to health care, food, housing security and education. Many were referred to the unit from their own homes, schools, foster care, State-run family homes and residences, or were transferred from other hospitals, child health clinics or hostels.

Some had speech or behavioural problems and exhibited trauma-induced coping methods including behaving disruptively or aggressively.[3] Very few had a valid diagnosis of an acute mental illness that required hospitalisation.[4]

Significantly, many, or even most, of the children and young people at the unit didn’t have a mental illness at all and never should have been placed at Lake Alice in the first place.

There was very little attempt to understand the real cause of the behaviours of those at the unit and staff got little support. Our inquiries show that it was likely that many admissions to the unit were unlawful. The Department of Social Welfare did not have the power to admit those in its care to the unit without the consent of the children and young people themselves. Certainly, admission as punishment or to relieve overcrowding in social welfare residences, would not have been lawful. The Department failed to obtain the consent of those detained or keep their whānau fully informed.

In the almost eight years the unit operated, Dr Leeks and the staff at Lake Alice inflicted, or oversaw, serious abuse – some amounting to torture – in what quickly became a culture of mistreatment, physical violence, sexual and emotional abuse, neglect, threats, degradation and other forms of humiliation.

The torture survivors experienced included electric shocks, often without anaesthetic, applied not just to the temples but to the limbs, torso and genitals. They were given excruciatingly painful and immobilising injections of paraldehyde, administered by staff as punishment or as an improper form of aversion therapy, not for legitimate medical reasons. Children and young people were held in solitary confinement and deprived of their liberty, sometimes for days or weeks on end.

The atmosphere in the unit was one of intense fear.

Dr Leeks said that he wanted to establish a therapeutic community at Lake Alice. Instead of addressing the unique needs and any underlying psychiatric difficulties of children and young people, Leeks set out to fix their ‘delinquent’ behaviour and treat what he perceived as their underlying psychiatric problems with aversion ‘therapy’, abusive acts and torture.

Lake Alice was not the therapeutic environment Dr Leeks said he wanted to create.[5]

Dr Leeks believed he could do what he wanted with those at the unit because many were too disruptive for Department of Social Welfare-run institutions and too destructive for the Department of Education.[6] Dr Leeks described them as “bottom-of-the-barrel kids”.

Dr Leeks wielded almost unbridled power over the nurses and staff at Lake Alice some of whom, in turn, misused their power against the children and young people in their care. There was a culture of impunity that enabled and normalised acts of abuse and torture. Sexual, physical, cultural and emotional abuse was widespread and unchecked in the unit.

Children and young people were psychologically and spiritually damaged by separation from their whānau, communities and friends. Māori and Pacific children and young people were not only deprived of their culture but endured racist taunts and harsher treatment because of their race. The lack of knowledge and inclusion of taha Māori or pacific concepts/taha Pasifika in mental health treatment led to survivors being over-medicated, labelled evil and sick, and further punished.

Although the Department of Education established a school at the unit, few received adequate education during the weeks or months they were there. Some were so affected by the electric shocks and other forms of abuse they were being subjected to that their ability to concentrate, learn and remember was severely compromised.

Far from being ’fixed’, those sent to the unit suffered from stress, anxiety, shame, guilt, fear, sorrow and anger. Māori survivors talked about the impact on their mana and mauri, and the whakamā, shame, of being at the unit. Most were deeply traumatised. They and their whānau still suffer from the effects of the trauma to this day.[7]

The impact of abuse, whether experienced or witnessed, has had severe consequences for survivors’ mental health. Some who had no mental distress before being sent to the unit have since been diagnosed with a mental health condition. Long-term symptoms include uncontrollable outbursts of anger, memory loss, hypervigilance and a persistent fear of being sent back to Lake Alice, even though they know the hospital has long since closed.

Many survivors reported becoming dependent on drugs and alcohol, sometimes from a young age, to numb the emotional pain and block out traumatic memories. As a result many have been convicted for drink-driving and cannabis use.[8] Some found the pain so unbearable they saw no option but to commit acts of self-harm or take their own lives.[9] Some survivors still carry physical scars and symptoms, including migraines and headaches from the electric shocks, back pain, and permanent bowel injuries from the sexual abuse.

Less visible, but just as painful, effects on survivors include the weakening of whānau and traditional cultural bonds. Many Māori and Pacific survivors had trouble reconnecting with their whānau, communities and culture on release from the unit. Most survivors have said they don’t trust others. They tend to be deeply suspicious of those in authority and have difficulty forming healthy, long-term, intimate relationships. This suspicion of authority figures, together with a poor education, has resulted in many survivors struggling to get or hold on to jobs. One survivor had to leave his job because the sound of workplace machinery triggered memories of the ECT machine Dr Leeks used to abuse him.[10]

The Department of Social Welfare did not routinely check that the unit was an appropriate place for those it sent there. Tamariki, rangatahi, their whānau and support networks had little or no ability to complain about the treatment at the unit. The Departments of Social Welfare and Education failed to act on complaints. Nothing was done to prevent the abuse suffered by those in their care.

None of the agencies that received complaints about the unit took effective steps to investigate and bring to account the perpetrators of the abuse. In the following decades, survivors tried repeatedly to hold Dr Leeks, staff and the responsible government departments to account. They sought compensation and redress for the torture, abuse and neglect they suffered through legal action, negotiation, public calls for inquiries and complaints to NZ Police.

The institutions and entities called upon to act included the Ombudsman, a commission of inquiry, NZ Police, the Medical Association, the Medical Council, the New Zealand branch of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, the Department of Health, the Department of Education, the Department of Social Welfare, Cabinet, Crown Law, the Health and Disability Commissioner and ACC. Despite all these attempts, the perpetrators were not held to account and survivors did not receive adequate holistic redress, or puretumu torowhānui.

Investigations had limited scope and resources. Court cases were defended even though, as Solicitor-General Una Jagose acknowledged, “the proof was right there in the file”.[11]

Settlements that were reached, beginning with 95 survivors in 2001 after years of gruelling negotiation with the Crown, were late and limited. They came with qualified apologies and confined redress to financial payments. They did not consider the restoration of the oranga, wellbeing of the survivors including the cultural needs of Māori survivors or Pacific survivors.

The most recent NZ Police investigation attempted to fix the failures of the three previous investigations. Charges were laid against one former staff member. However, the passage of time meant it was too late to lay charges against Dr Leeks and other suspects because they were either dead or too elderly and infirm to face charges.

Ultimately, Dr Leeks was never held criminally accountable before his death for the abuse he inflicted on so many vulnerable children and young people. In 2020 (on a complaint by Paul Zentveld) and 2022 (on a complaint by Malcolm Richards) the United Nations Committee Against Torture found that Aotearoa New Zealand had not undertaken a prompt, impartial and independent investigation of allegations of torture at the unit or provided appropriate redress.

The children and young people at the unit were out of sight and out of mind. They were tortured and abused. Survivors, their whānau and communities suffered incalculable, lifelong harm at the hands of so-called professionals. Like all inquiries, this Royal Commission does not have the power to make findings of criminal or civil liability—only the courts can do that. But from the earliest days there was evidence to justify criminal charges against Lake Alice staff, and our investigation has highlighted failings in the police investigations in the 1970s and 2000s.

It is wrong that no one has ever been held accountable and that survivors are still waiting for justice. The story of the Lake Alice child and adolescent unit is a shameful chapter in the history of Aotearoa New Zealand. It must be faced head-on, without excuses or explanations, and with a determination to make proper amends and ensure such tragedies never happen again. Recommendations for change will be made in the final report.