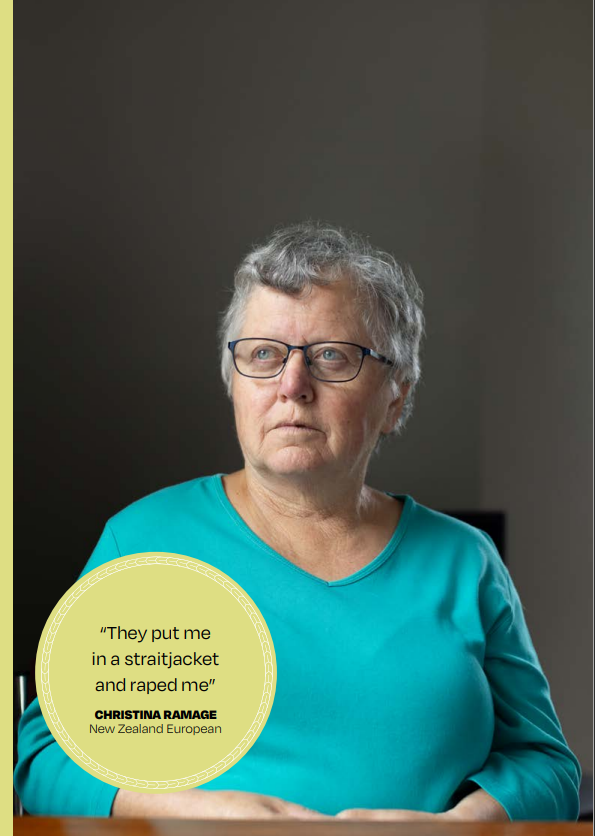

Survivor experience: Christina Ramage Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Name Christina Ramage

Hometown Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

Age when entered care 15 years old

Year of birth 1956

Time in care 1971–1976

Type of care facility Psychiatric hospitals – Ward 10 Auckland Hospital, Carrington Hospital.

Ethnicity NZ European

Whānau background Christina has a younger brother and a younger sister.

Currently Christina lives in Auckland and says her counsellor is a lifeline for her.

I was 15 years old and a friend and I went out to celebrate passing School Certificate. That night, I was raped by five young men. They were at a bus stop and threatened me, dragged me around the back, then raped me. I remember bits and pieces of what happened, but other parts are blank. I kept it to myself, but soon afterwards I started cutting myself because I was so stressed.

I was also sexually abused by my father from when I was a pre-schooler until I was 13 years old. A lot of what I remember from this time is being in darkness. I was afraid most of the time because I didn’t know what was going to happen. I became more and more stressed and ended up having seizures.

I was 15 years old when I was admitted to psychiatric care, first at Auckland Hospital. A doctor there gave me something he described as a “truth drug”, then I went before a three-person panel and they decided I was a danger to myself and to the public. I was committed to Carrington Hospital as an involuntary patient. The doctor had said I would be told the results, including what I had said, but that never happened. It makes me angry, because it seems like they decided to commit me because of what I’d said, but they wouldn’t tell me what I had said.

I was sent to Carrington Hospital in 1972, at 16 years old. I was taken to a dark and smelly room and told to get on the bed. They gave me electric shocks without anaesthetic. Then I was admitted to an unlocked ward for women, but later moved to a locked ward called Park House.

My sister told me the entrance to Carrington was nice and welcoming, with a picture of Jesus on the wall. But that wasn’t the case with the wards – they were terrible, overcrowded and understaffed, and I was treated as a lesser human being. The bedrooms had bars on the windows. The reception and entrance were a facade.

I was given a lot of drugs but never told what they were or how I might react to them.

It was a known thing that the male nurses at Carrington were university students working for wages in the semester break, so a lot of them were totally untrained. In the female ward, women were there to be used for sex or assault. People seemed to think it was easy to look after a lot of ‘loonies’. These untrained nurses had direct access to straitjackets and were allowed to use them on us without having to give any reason.

One day I was walking down a corridor when two young male nurses grabbed me, took me into an area behind doors where the straitjackets were kept, and put one on me hurriedly and roughly. I was confused and afraid; I didn’t know what I’d done wrong, and I was terrified of whatever was going to happen.

They laughed and joked. “Nobody can see us here,” one said. They pushed me onto the ground, and I thought, “This is it”. I realised what was about to happen, and it terrified and panicked me. I struggled uselessly to get out of the straitjacket even though I knew I couldn’t. I closed my eyes, I was overwhelmed and despairing.

As one raped me, the other would say, “Hurry up, hurry up”. I was raped by both of them. I could feel my body above my waist, but not below at all. I screamed out even though I knew it was no good – my cries couldn’t be heard through the thick and solid doors that hid the three of us.

After the rape, the two of them sat on the steps and laughed at me for what seemed like forever. “She’s no good, scum, rotten to the core,” one said. They took the straitjacket off and I straightened my nightgown. I didn’t say anything – after all, who would believe a mental patient who had previously been abused and raped and was currently in a mental asylum? They’d probably say I was asking for it, or I was lying. I knew if I said something, I’d be locked up.

I was sexually abused by a psychiatrist while I was at Park House. A nurse took me to a very small room and the psychiatrist locked the door. He asked me a few questions. One of them was, “Do you like sex?”. I thought he’d find something wrong with me if I said no, so I said yes. The nurse took me to the examination bed and left the room, and the psychiatrist took my underwear down and raped me.

A few months after the psychiatrist had raped me, a nurse took me to a room that was usually always locked. The room had lots of shiny things. They told me to get on the bed, and suddenly everything went dark. The next thing I knew, I was awake. “It’s okay, you haven’t got a baby anymore,” a nurse said. I realised I had been given an abortion following the rape by the psychiatrist.

I think this is one of the most criminal aspects of my time at Carrington. It still haunts me today.

I was also sexually abused by other patients. Three young women assaulted me, two of them on either side fondling my breasts while the other one pushed a finger up my vagina.

I also saw other people being abused or neglected in the same way that I was, and it created an atmosphere of abuse and neglect that was thick. A female patient once got hold of some matches and went to her room during the day and set fire to herself on the mattress. I never saw her again. The incident really troubled me because she was in quite a helpless situation – she had been ‘dumped at the door’ at birth as she was disabled.

I became wary of what was going on around me, and I trusted no one. All-enclosing fear was everywhere and hung really heavily. The feeling was palpable all the time.

I was given 10 rounds of electric shocks, six shocks per round. I wasn’t told how this would be done, what might happen to me afterwards as a result, or why I was being given the shocks. I wasn’t given a sedative or anaesthetic on any of these occasions, and wasn’t even told that this was a possibility. ECT was often given as a form of punishment.

I had to get onto the bed and the nurses would put a cloth in my mouth while they held me down. The doctor would say, ‘are you ready’ and flick the switch on the grey ECT box. After ECT, I was always sore in my private parts, and I realised I must have been raped or sexually assaulted.

You got one bath per week, as the sole female nurse came in only once a week. She would watch you having a bath. The baths were made of rough concrete and the water only covered the bottom half of your body as you laid down.

The wards had padded cells and you were thrown into them as punishment if you played up. I was thrown in there for making a noise scraping my chair as I got up in the dining room. The reasons for locking us up were many, and petty.

I was generally unable to express myself, so when I did, it was in the form of fighting. The male nurses would throw me into a room and take apart the three-piece bed, leaving only the mattress. They’d pull my pants down and roughly inject me with a knockout drug, and leave me in there for a long time. It was usually dark when I went in and daylight when I came out, except for the occasions when I was left in there for longer than a day.

Going into psychiatric care was the end of any education I received. I didn’t get any schooling, although a few people did, if they were considered ‘well enough’. Sometimes an occupational therapist would come in, but there was no entertainment and nothing to do.

I was 20 years old when I was discharged from Carrington. My hopes and dreams were shattered. I was angry, bitter, sad, and I felt alone. It was like being in a straitjacket all the time.

It is encouraging that, after 37 years in my case, a Royal Commission of Inquiry has finally taken steps to seek to uncover the harrowing stories of many individuals who were in care. It’s long overdue.

I’ve spoken out for the people who are currently in psychiatric wards, and for those in the future. My experience shows that there is always hope.[382]