1.1 Context He horopaki

1.1.1 Ngā Wairiki me Ngāti Apa

1. Our starting point in seeking to understand the story of Lake Alice Psychiatric Hospital is with the whānau, hapū and iwi of Ngā Wairiki and Ngāti Apa. These iwi are mana whenua and are inextricably linked to each other and to the whenua on which the hospital formerly stood. A team of iwi researchers provided the history of the Lake Alice whenua to us.[13] The full report is available from our website. What follows is a summary of that important history.

2. The Lake Alice area was known as Rotowhero and formed part of an extensive area named Otakapou that contained several dune lakes and associated wetlands. These lakes and wetlands provided the iwi with mahinga kai, including freshwater mussels, tuna, eel and waterfowl. Ducks were taken in large numbers during the moulting season. It became a heavily populated, resource-rich area, containing kāinga, a palisaded pā known as a pā kai riri, wāhi tapu and extensive cultivations. Ngā Wairiki and Ngāti Apa tūpuna treasured these dune lakes and surrounding whenua for the valuable resource it was, sustaining the iwi with its bounty.

3. In May 1849, Ngā Wairiki and Ngāti Apa entered into a transaction with the Crown that resulted in most of their land between the Turakina and Rangitīkei Rivers transferring to the Crown. In 1919, Mr Horace Wilson purchased an extensive area, including most of Rotowhero Lake Alice, from the Crown, after returning from the first World War. He named his farm ‘Rotowhero’, taking the iwi name for the lake.[14]

4. The area to the north of ‘Rotowhero’ farm formed a part of the extensive Heaton Park Estate, which included several dune lakes associated with Otakapou. In 1938, the government acquired 541 acres of this land to be used as the site for a psychiatric hospital. The hospital site abutted Rotowhero Lake Alice and included Lake Hickson and part of Lake William. It was anticipated that Rotowhero Lake Alice would be the main water supply for the hospital.[15]

5. At the time of the transfer to the Crown, a 100-acre block called Otakapou was reserved for iwi. This reserve is about two kilometres west of Rotowhero Lake Alice and a little to the south of Lake Heaton. It took in the western part of Lake Bernard and contained urupā, cultivations, pā tuna and an important fishing camp on the western shore of the lake.

6. The Crown’s representative debated with Ngā Wairiki and Ngāti Apa leaders about how much land should be reserved from the transfer. The parties eventually agreed to a reserve of 50 acres (which was later found to contain 100 acres).[16]

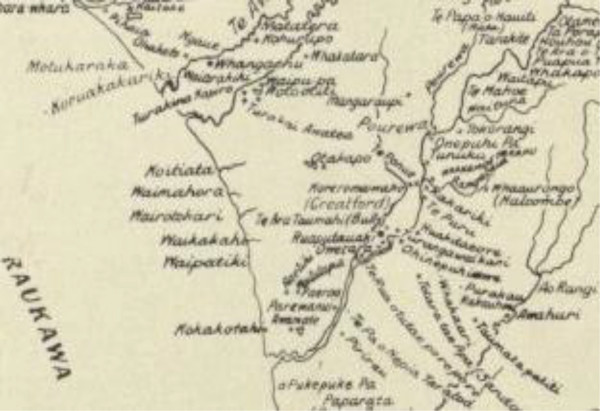

‘Otakapo’ [sic], shown on a map from T Downes.[17]

‘Otakapo’ [sic], shown on a map from T Downes.[17]

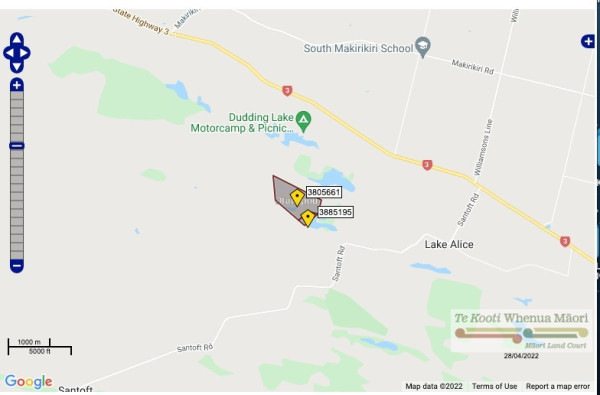

7. Today, 39.9397 hectares of the Otakapou reserve is administered by an Ahu Whenua Trust, representing 140 Ngā Wairiki and Ngāti Apa individuals. A smaller area of 4.4214 hectares, taking in part of Lake Bernard, is a Māori reservation established in 1978 “for the purpose of a fishing ground and recreation ground for the common use and benefit of the owners and their kinsfolk”.[18] The two areas are shown on the map below, sourced from Māori Land Online. The second map shows the proximity of Otakapou reserve to Rotowhero Lake Alice.

Map 1.

Map 2.

Map 2.

8. From the time of its construction in 1950 to its closure in 1999, Lake Alice Hospital became a prominent feature on the landscape, visible from State Highway 3. For Ngā Wairiki and Ngāti Apa, it became a blot on the landscape in more ways than one. Not only was the hospital built on land the iwi want returned, but it also came to represent another component of colonisation. It was a place that classified their people as ‘mentally unwell’ when they sought or needed support, understanding and healing. Their ‘treatment’ took no account of Māori perspectives on health, spiritual beliefs or taha wairua and, in many cases, made them worse.[19]

9. Whānau members who had been residents at Lake Alice, even for a short time, reported knowing that things were not safe there for everyone. They were aware of the tūkino (abuse, harm and trauma) occurring, reflecting the inhumane environment they were in, and how it increased the risk of further harm and distress to them. Whānau members who worked in the hospital and witnessed the tūkino occurring reported feeling powerless and hoping someone in authority would do something to stop the tūkino.[20]

10. Lake Alice was yet another example of the historical tūkino the people of Ngā Wairiki and Ngāti Apa suffered from the State and its institutions.[21]