Hake Halo

Name: Hake Halo

Age when entered care: 13

Age now: 60

Hometown: Niue

Time in care: 1971-1972; 1975-1977

Type of care facility: Psychiatric hospitals, boys’ home

Psychiatric hospitals – St Johns Psychiatric Hospital, Lake Alice, Carrington Hospital; boys’ home – Ōwairaka Boys’ Home.

Ethnicity: Pasifika (Niuean)

Whānau background: Niuean family, came to New Zealand when Hake was six.

Hake Halo

Hake Halo

They’d read your mail, at Lake Alice, and if you wrote home telling your parents what was happening – the drugs, the electric shocks – they wouldn’t send the letter. So I figured out a way around that, to let my parents know what they were doing to us.

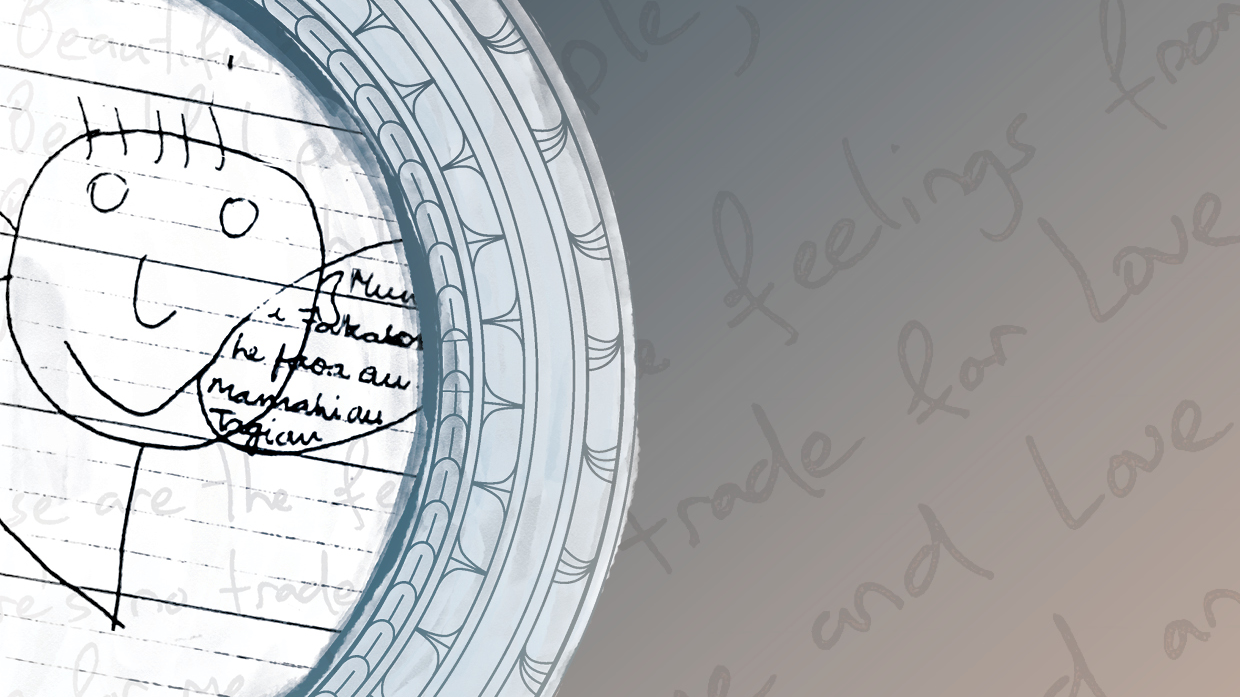

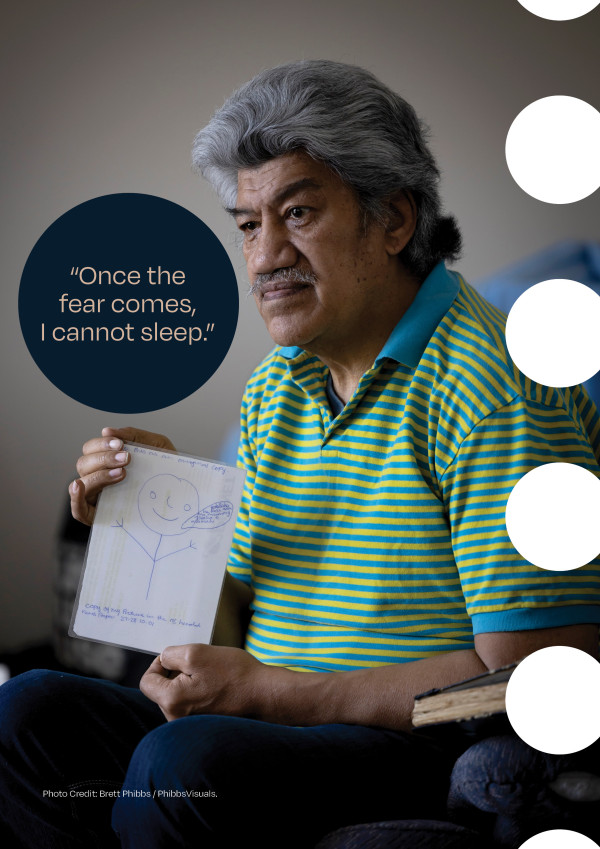

We had to write our letters in English, so I would do that saying everything is alright, but I would add drawings of stick figures looking happy, with speech bubbles in Niuean: “Fakasoka he faoa au, mo huki au, mamahi, tagi au” – “Mum, the people are giving me electric shocks and injections, it’s painful, I’m crying”. But because the stick figures looked happy, they didn’t take any notice, and they let the letters go. I had to do this about six times before she got the message.

My mother tried to get them to stop, but she felt powerless, and the language barrier was always a problem – not just for her, but for me, too – that’s how I ended up in Lake Alice in the first place.

I was born in Niue and raised by my grandparents, which is normal in my Niuean culture. I was six when I came to New Zealand and I didn’t speak a word of English. My father knew more English than my mother, but not much. At school I didn’t understand anything, and because I didn’t speak in class, they thought I was intellectually disabled and I was put in a special class. One day I was being a nuisance and the relief teacher that day dragged me out of the classroom and locked me into a dark room. I was upset and angry, and I tried to push on the door to open it. My hand accidentally went through the glass door and I cut my hand badly.

I was perceived as being violent because of this and was admitted to a psychiatric hospital in Auckland. My parents weren’t happy about it and with the help of a Niuean reverend they got me out.

My dad died, and I started playing up and getting into trouble. I went to Ōwairaka Boys’ Home, and from there a doctor decided I should go to Lake Alice. My parents weren’t told it was a mental hospital, and there were no Niuean interpreters to help. She only signed the papers because they said they were taking me to a school.

I thought Lake Alice looked like a prison, not a school. I was given medicine immediately, and they didn’t say what it was for – but from my notes I know I was given five different drugs.

Then I met Dr Selwyn Leeks, who gave me electric shocks. I had a funny feeling something was not right. They didn’t explain anything or ask me questions, they just put me on the bed. He put a mouthguard in my mouth. You would end up biting your tongue off if it wasn’t for that mouthguard.

I felt like I was being whacked with a sledgehammer at full speed. My memory is that Dr Leeks turns it on and it hurts, and your body is forced into a sitting-up position because of the pain, then he turns it off and you fall back onto the bed. My body bounced on the table and I was crying. It was like two huge knives being driven into my head, and I was very afraid. Afterwards, I would have headaches, memory loss, anger and fear.

I would beg Dr Leeks not to do it again but he didn’t care. He was a man full of hatred.

We always knew if someone was getting electric shocks because we’d heard the screams coming from upstairs. Even the workers who were there, they were doing their jobs and crying at the same time because they knew what was going on.

I also got paraldehyde injections, which they gave you for bad behaviour. I was given it every week, and once just for laughing too loudly. You would have to pull your pants down and they would give the injection above your buttocks. Then it felt like having a burning steel bar up your backside. Afterwards you would be crying and walking as slow as a tortoise, and the other boys knew you’d had paraldehyde. It made your breath smell straight away and you couldn’t sit down because of the pain.

It was like getting a hiding. Instead of staff using their hands, they would use paraldehyde to protect themselves from allegations of assault. That is how clever they were.

I was allowed to go home for Christmas but then something terrible happened. I was asleep in my bedroom and my sister was murdered by her boyfriend in the room next door. I was the first person to her room and I found her dead. She was holding her baby at the time he murdered her, and the knife was lying on her chest. I had no support and no-one to speak to. I got upset and got into more trouble, ending up in Youth Court.

There were no interpreters there and I was placed under guardianship. The social worker misunderstood my mother – she asked him to please look after me, while I was in care, but they thought she was saying to take me and make me a State ward. If a Niuean interpreter had been there, it would’ve changed a lot of things for me.

I was returned to Lake Alice. I was angry and not coping. But there was a staff member there, Anna, who helped a lot. She thought I was ‘bad’, not ‘mad’, and gave me counselling, advice and encouragement. Her way of helping was way better than drugs and electric shocks.

I was 14 when I got out of Lake Alice, and it was a relief to be away from the shock treatment.

I would’ve had a normal life if I hadn’t gone to Lake Alice. It’s been hard to hold down a job. I suffer from anger, fear, forgetfulness, hearing voices, stress, confusion and much more. I had had epilepsy as a baby and the electric shocks made it come back, plus I had developed a big problem with my temper. I have nightmares a lot about the torture and I don’t feel safe sleeping by myself in my own bed. Lying on my back makes me think about getting ready to have electric shocks and once the fear comes, I cannot sleep.

Dr Leeks said that I was like an ‘uncontrollable animal’. I would say that he is the uncontrollable animal to have done this to me and hundreds of other children.

I am speaking up now as I am doing it for the others who cannot speak for themselves. I would like people to acknowledge what happened at Lake Alice, because I feel people do not believe me.

One of my brothers got me into his church where they support people with healing prayers. I’ve been going to that church since 1978 and I’m now an elder there. My faith has really helped me in trying to move on from what happened. Just like in the Bible, in Philippians 4:13: “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.”