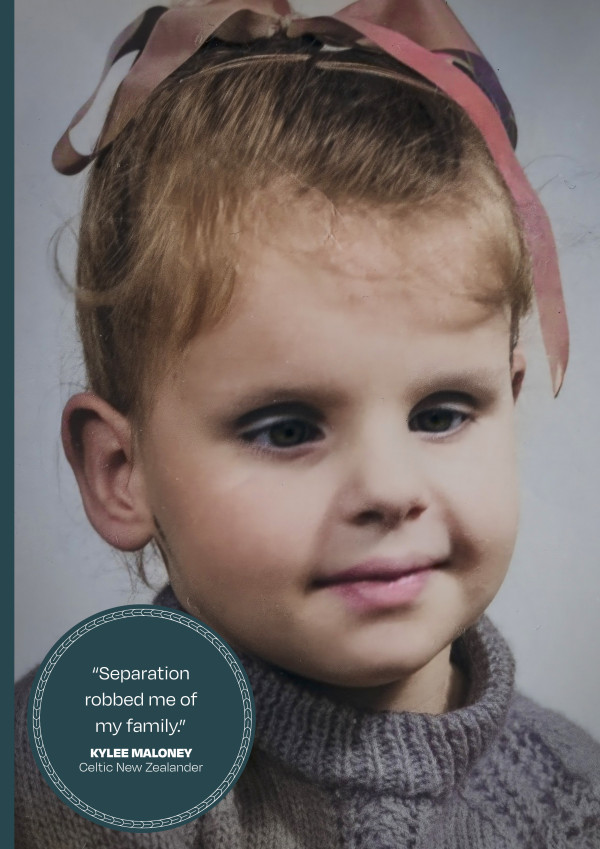

Survivor experience: Kylee Maloney Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Name Kylee Maloney

Hometown Te Papa-i-Oea Palmerston North

Age when entered care Almost 5 years old

Year of birth 1966

Time in care 1971–1985

Type of care facility School for children who are blind or have low vision – Homai College in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, run by the Royal New Zealand Foundation of the Blind.

Ethnicity Celtic New Zealander

Whānau background The youngest of three children, Kylee has a brother and a sister.

Currently Kylee lives with her sister in Palmerston North and they are very close.

I was born prematurely and spent the first two months of my life in an incubator, tube-fed and pretty much never touched unless professionally required. That’s had a lifelong impact. I became blind from being in the incubator - having too much oxygen scarred the retinas of my eyes.

I was a fairly confident child, but I didn’t stay that way. It all changed when I went to Homai.

I don’t remember any conversations about why I was going there, and I don’t think I even really knew what Homai was. As an adult, I asked my parents about it. They said it was something expected of them from both medical professionals and society itself. They were just told that Homai was the best place for me, as a blind person. It was a specialist school and residential campus for kids who are blind or have low vision.

I was there for over 14 years, from just before my 5th birthday. I felt bewildered and, was left to fit in. Nobody explained anything to me about what was happening. Initially I’d go back home on the weekends, then only in the school holidays. I’d tell my dad I didn’t want to go back, but the conversations were fruitless. I learned in the end not to be demonstrably unhappy about returning, as it made my parents unhappy. I was told that I couldn’t be unhappy at Homai as I was a nuisance and being there was the best place for me to be.

There was a lot of psychological and emotional abuse. I used to have my hands tied behind my back for touching my eyes, and I was only 5 or 6 years old at the time. Lots of the children touched their eyes, because we could see pin lights when pressure was put on them. I suppose the matrons thought it was socially inappropriate. After a while I figured out how to untie myself, and once I could do that, I didn’t get tied up as much.

If we got a package from home, it all got pooled and we’d have to share our things with the other children. Nobody explained why and I felt resentful about this. I also knew that some of the staff were dipping into our gifts, because we’d open our parcels and some of the things in there, it would disappear.

When I was very young I used to regularly get develop fevers, where my temperature would go up, but I don’t recall ever getting without the associated symptoms of cold or flu or feeling unwell. I think they were psychosomatic, a way of dealing with what I was experiencing at Homai. The staff, though, thought I was putting it on. The matrons were trained nurses and should have known the symptoms for what they were, but I think they chose to see me as a nuisance for ‘faking illness’ instead of trying to discover the cause.

I had an incident in the pool when I panicked and was hauled up by somebody, and after that I was too afraid of water on my head to have my hair washed, so whenever it was time for hair washing, I fought and struggled. In the end, they wrapped me up in a sheet to force me to submit. It was like a straitjacket –– effectively, that’s what it was.

I struggled with food at Homai. There were things I didn’t want to eat, some of which I was intolerant of, and staff exhibited a lot of power and control when it came to food. I wouldn’t submit and eat what they wanted me to eat. Hostel staff would hold my nose and force my mouth to open and make me eat whatever it was. I refused, it would make me sick, and I would try to run away.

We had to eat everything we were given, but then we were punished if we put on too much weight. Our food would then get restricted –– it was all very arbitrary. To rebel, I just wouldn’t eat. So my eating became very erratic.

I was so positive and confident before Homai. I was removed from my home at such a young age, and there was no respite from what I was experiencing. The whole ethos at Homai was that if you were not meeting expectations, you were somehow less of a person. You were accorded less respect.

By separating me from my family, we were robbed of the opportunity to learn from and grow with one another. Separation robbed our families of the learning and growth experiences they would have had in learning to live with, and advocate for us. Separation robbed me of the ability to successfully relate to my extended family – and to have successful close relationships with anyone.

It had a big impact on my relationship with my mother, and we had a difficult relationship throughout the remainder of her life. We never bonded – we weren’t given the opportunity. I always had the feeling that her emotions and feelings were more important than mine. Not being unhappy at Homai was as much, if not more, about her own guilt as it was about my needs.

I remember her once casually telling a friend, while I was sitting with them, that she had thought that if she had killed me when I was about three or four, everything would have been alright.

I already had relationship issues when I arrived, and Homai exacerbated them. I’m now sitting here, avoiding society unless it’s on my terms. It has coloured everything I am and everything I do. I feel that being inside my head is the only safe place to be.

The general impact of my life’s beginning and my Homai experience has been loneliness. The knowledge that I am, and always will be, an outsider, is both liberating and painful. Liberating in the sense that this process has given me permission to try to reverse the habit of a lifetime and stop trying so hard to fit in and be accepted, and painful because I long, like anyone else, to belong somewhere and be loved.

People like me who are congenitally blind are outsiders, anyway, as we are so much in the minority. Most people are partially blind or have lost their sight later in life. I’m in the minority of the minority.

The pressure to be independent that was so prevalent at Homai has stayed with me all my life. Even today, I feel like a loser because I live with my sister and not by myself, doing everything for myself.

Along with many other parents, my mother and father entrusted care of me during term time to the Royal New Zealand Foundation of the Blind, in my case for more than 14 years. This organisation had a responsibility to ensure that all our needs – physical, spiritual, intellectual and mental – were met, so that we would grow up well-adjusted and prepared to live successfully in a hostile world. They failed to ensure this.

The medical profession encouraged our parents to hand over their ‘problem’ children to the care of others, informing them that ‘experts’ were better placed to care for them than they were. These people weren’t experts – they were largely untrained and unqualified, and universally poorly paid.

Homai could have been a nursery where us we tender seedlings were nurtured in the arts of relationships and family, as well as taught how to do all the physical things anyone needs to do on a daily basis, so that we could have been prepared to contribute to, love, and even make a difference in the wider world. Instead, it was a confusing, sometimes cruel, competitive and discouraging environment where, if we learned any intangible quality with which to move forward, it happened by accident.

With the new Ministry for Disabled People on the way, with its ‘Enabling Good Lives’ principles at the forefront, I would like it recognised that a ‘good life’ for me, as a survivor, is not to push me out into a hostile world and demand that I work. It is to keep me comfortably independent, secluded and safe. That, to me, is my ‘good life’ – the only one I’ll survive. I wish it could be different.

For all that I’ve achieved and tried to achieve, I feel like a failure because I can’t live in your world.[216]