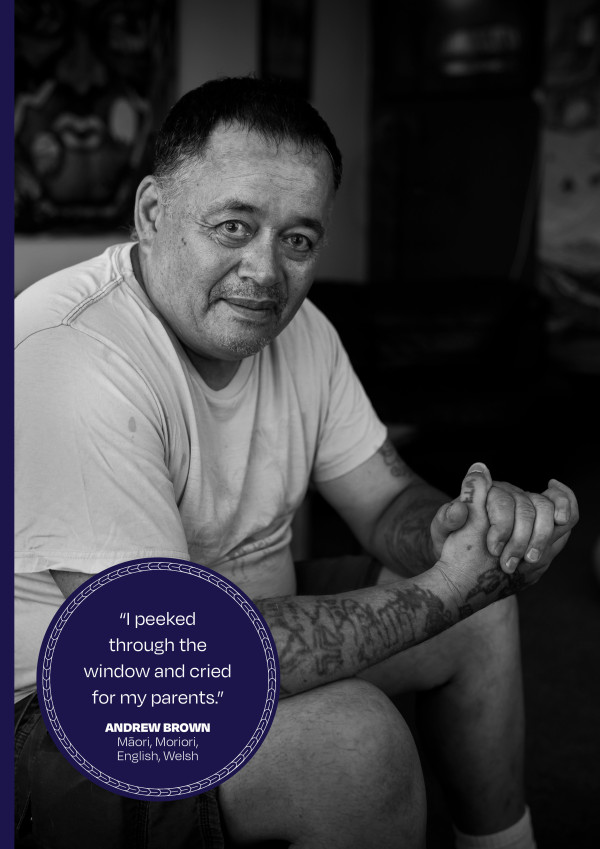

Survivor experience: Andrew Brown Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Name Andrew Brown

Age when entered care 9 years old

Hometown Te Whanganui-ā-Tara Wellington

Year of birth 1960

Time in care On and off from 1970 to around 1988

Type of care facility Berhampore Family Home; boys’ homes – Epuni Boys’ Home in Te Awa Kairangai ki Tai Lower Hutt, Hokio Beach School near Taitoko Levin, Holdsworth Boys’ Home in Whanganui, Ōwairaka Boys’ Home in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland; psychiatric hospital – Oakley Hospital in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland.

Ethnicity Māori, Moriori, English, Welsh

Whānau background Andrew’s mother is Māori and Moriori, from the Chatham Islands, and his father is of English / Welsh descent. He has five older brothers and two younger sisters.

Currently Andrew is a single parent and is also raising a family member, who has been with him since birth.

I’ve been waiting for this chance to share my story and reclaim my voice.

I was nine years old when I was taken from home by a social worker. My file notes that I was the subject of a Court Order for not being under proper control. Social Welfare didn’t even bother to explain why they took me away from my family. But I’d been wagging school a bit and fighting – I’d stayed for nearly two years with my grandparents on the Chatham Islands and didn’t seem to fit in at school back in Wellington. I also experienced racism at school. I didn't realise at the time that's what it was, I just knew that I had to fight back. That's why I was in the principal's office all the time.

My first placement was a Presbyterian Family Home in Berhampore, with lots of other kids all under 14. I remember being the only brown kid at the home. There was a lot of praying and I was forever cleaning shoes – I must have cleaned 40 to 50 pairs a day. I was sexually abused by the older girls. I was sad, lonely and miserable, and I just wanted to go home to my family. I tried to run away with some other boys, but the police stopped us and took us back.

After that I was taken to Epuni Boys' Home in Lower Hutt. I was 10 years old. They put me in the secure unit – a concrete room with holes in the wall, windows that you couldn’t close. The room was concrete with a plastic cover on the mattress and pillow. There were holes in the wall, windows that you couldn't close. I didn't know what was going on. I remember peeking through the window crying for my parents.

The room reminded me of a prison – it was horrible. I remember feeling cold and listening to the sound of the wind howling all the time. You were only allowed out of your cell for one hour. So, you basically went from standing in one concrete room to another.

I think I was in secure for about 10 or 14 days. I felt totally isolated – I remember hearing kids screaming, yelling and crying outside, but I couldn’t actually see anybody. I don't recall any books and anything to read – all you could do all day was sit there and stare out into a field. I was abused by the staff, but I felt too afraid and unsafe to say anything to anyone about it. I thought I was going to die in there.

At Epuni, we were forced to clean volleyball courts with a toothbrush – they took two weeks to clean. We had to mix up a big drum full of caustic soda to clean them with. The staff would make us stand in it and the acid would eat the skin off your feet. We spent all week cleaning, folding clothes and working in the kitchen. On Saturdays we played sports whether you liked it or not. I was small for my age and often the youngest, so sports would be very brutal for me.

Some of the staff were sexually abusing boys. One of them came into my secure unit and tried to comfort me when I was crying. He sat me on his knee, tried to cuddle and feel me too. He and other staff used to go around and visit all the boys’ rooms. They would come into the shower block and say they were checking to see if our balls had dropped.

I didn’t go to school while I was at Epuni, school was only for when "you are good". I tried to run away a couple of times, so they stuck me in a cage, like I was cattle. After another attempt to run away, they stuck me in the pound and I was beaten to a pulp. The beatings I endured were severe and savage. After a while, I was sent home to my parents. By then I was feral, I felt like I was constantly fighting for survival. Epuni taught me how to fight and when I went home my behaviour was the same. It was no good putting me into school, I had missed so much education and would fight anyone who came at me. Eventually I ended up back in Epuni.

When I was 10 or 11, I was transferred to Hokio – another State institution run by bullies and nasty people. The violence was severe, and a couple of times I nearly died. I was constantly fighting to keep myself safe from violence and sexual abuse by other boys.

After a few months I was transferred to Holdsworth. It was a ‘survival of the fittest’ mentality there – we all made knives to protect ourselves. I remember the staff and social workers at Holdsworth by the abuse they inflicted. It is unlikely that there was a single person employed there who could claim they didn’t know about the emotional, physical and sexual abuse. I saw a lot of boys mentally break at Holdsworth. For me, I turned to violence – there was no one to talk to about the abuse, so the only thing I could do was to pick up a knife.

I spent what I thought was about two years in total at Holdsworth. During that time, I was sent home. I had been there over a year before I got to go home. When you’re 11 years old, not being able to see your family is lonely and isolating. At home, I went to the local intermediate school, but I was struggling and couldn’t integrate, I couldn’t read and write very well – I had spent years cleaning, scrubbing and folding laundry instead of getting an education. I used to love learning and was considered intelligent by the teachers in my younger days, but I wasn't coping at school because the State deprived me of an education.

After my second stint in Holdsworth, my father was transferred from Wellington to Auckland because of his job and we moved up there. I’d got involved in stealing cars – I was pretty much stealing cars every weekend, and making good money too. It wasn’t long before I ended up in Ōwairaka Boys’ home. I was 14 years old.

Ōwairaka was a nasty place, and like other State-run institutions I had been in, there was a kingpin system ‒ a pecking order based on size and how mean and nasty you could be. Housemasters not only encouraged this, they set it up and used violence and aggression to control you. At Ōwairaka, the staff organised a boxing ring with the biggest, meanest boy, built like a huge gorilla. They made us fight like adults – I knew I was going to get bashed and fought as hard as I could. If you complained the staff would bash you. There were no doctors or nurses around. It was the sort of place where you had to harden up.

I had no voice at Ōwairaka, but when I got out I told my parents about what had happened there. They went to the police, which is what you are supposed to do, but the police refused to believe them. We felt helpless, like we had no voice. I turned to drugs and alcohol to numb the pain I felt.

I ended up overdosing a couple of times and getting in trouble with the police for petty crime. I was 17 or 18 when the court ordered me to be sent to Oakley Hospital. I was there because I was using drugs and booze to numb my pain. It was another abusive place, with staff who hit, hurt and abused patients. They diagnosed me with schizophrenia, but I think the doctor was just saying whatever he needed to, to tick the box.

The staff would load you up with prescription drugs and say “just take them” when I asked what the drugs were for. They’d walk around with jars of pills and just give them out like lollies. I got addicted to the pills and would manufacture symptoms to get more. I became quite resourceful and could manipulate the doctors to prescribe whatever I needed.

Sexual abuse there was horrific – there were guys getting raped every single day by other patients. Staff knew what was going on and didn’t do a thing about it. Staff threatened us with shock treatment or they would make threats to send us off to Lake Alice.

I felt too unsafe to talk to the authorities about what I’d seen, I didn’t think they’d believe me, and there were no complaint processes.

I spent the bulk of my youth locked up in in State institutions. I was incarcerated into Mt Eden when I was in my mid-twenties. All up, I did three stints inside, including at Pāremoremo because I had escaped from Mount Eden Prison. During my time in prison, I’d regularly meet up with the boys I had known in the boy's home.

I continue to bear the scars of the physical and emotional torment inflicted on me by the State’s failure to keep me safe. I had no voice. No-one listened to me or believed the horrors I experienced as a child.

I was entitled by the State to an education. I didn’t receive one – I had to educate myself by reading lots of books. I have experienced an enormous amount of racism right throughout my life.

My relationships with other people don’t last, so I prefer to work with plants. I worked at Auckland City Council, eventually becoming the head gardener at Western Springs managing six different gardening teams.

The institutions I was in were brutal, and I feel fortunate that I survived. What happened to me in care has affected me throughout my life and made me determined that no child of mine would ever end up in State care. Despite the failure by the State to take care of me, I raised my son without any support, and he’s a good man.

No child should be taken off their parents. Don’t put a child in a concrete box with rusted bars and expect some white guy to have empathy for the little brown boy. We were taken from our whānau by the State. No one should have to experience what I went through.

Children have the right to be cared for, to be loved, to be protected, to be valued. If someone had made the effort to treat me as a person, rather than as a little brown boy, there could have been a totally different outcome. I often wonder how I might have turned out if I was given some better opportunities. I could have won a gold medal.[445]

Footnotes

[445] Witness statement of Andrew Brown (13 July 2022).