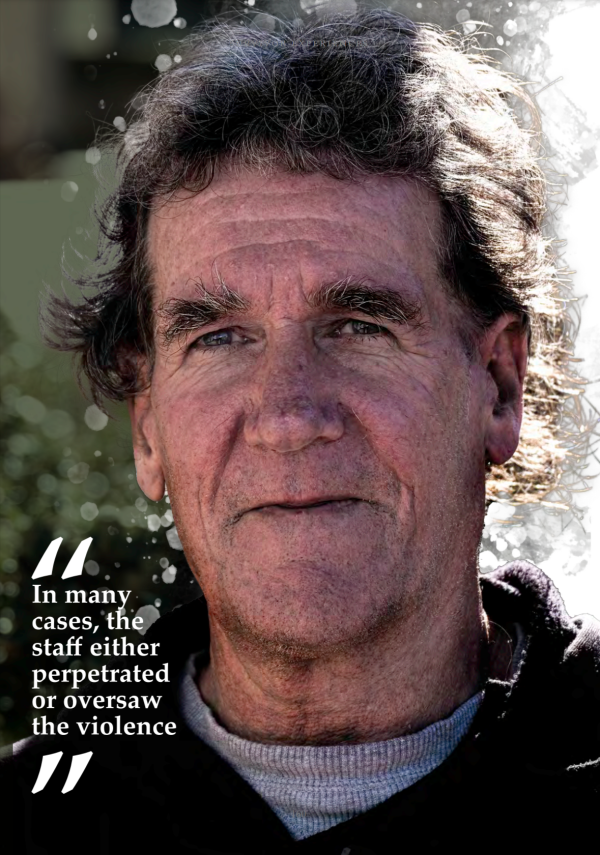

Survivor experience: Keith Wiffin Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Age when entered care: 11 years old

Year of birth: 1959

Type of care facility: Boys’ homes – Epuni Boys’ Home, Family Home

Ethnicity: Pākehā

Whānau background: Keith lived with his mum and dad, two sisters and a younger brother. Keith’s dad passed away suddenly when Keith was only 10 years old.

I went into State care after my father died on his 39th birthday, leaving a mother trying to care for four children with very little income or support. I was 10 years old at the time. I had two sisters and a younger brother. My mother was not able to care for us after my father’s death. That, plus my reaction to my dad’s death, led to the decision to place me into care.

There was a brief court appearance, and I was placed in State care. Next thing, I was in a van being driven to Epuni Boys’ Home, Lower Hutt. For the next nine months I had very sporadic contact with my family. It was hard to have any contact, even to write letters, and contact was not encouraged.

My introduction to the culture at Epuni started in the van on the way out there. There were a lot of other children in the van. One boy in particular didn’t like the look of me, and smashed a guitar over my head. I walked into the place picking bits of wood out of my head - that was my welcome.

The culture was violent and abusive. The boys had what they called a “kingpin” system. Fights and bullying were routine. I personally had broken bones and required medical treatment, including stitches.

It was a devastating experience to go into that, coming from a loving home and trying to deal with losing my father. The culture of violence was totally foreign to me. There had been nothing like that going on at home – we faced hardship, but there was never any abuse.

In many cases, the staff either perpetrated or oversaw the violence. The house masters were all very violent themselves. They wouldn’t hesitate to use physical violence. I saw a fair bit of that. Psychologically they made it quite clear we were second-class citizens and the most likely outcome in life was that we would go to prison. There weren’t many positive messages. It was an abusive and negative environment. Once you were in it, there were huge obstacles to success. We became products of an environment overseen by the staff.

The staff encouraged the kingpin system and used it as a means of control. The kingpin himself would be respected by the staff and used. If they thought somebody needed sorting out, they would turn to the kingpin to get that done.

I remember a camp in the Akatorua Valley. There were three cabins and there were fights going on in each cabin to determine who would be the kingpin. I was involved in a couple of those fights and my hand was broken. The whole process was overseen and encouraged by the staff who were there.

There were some serious child abusers working at Epuni when I was there. I will never forget being locked in a room in one of the wings and hearing the boy next door being raped by a staff member, knowing that that was happening and wondering when it would be my turn.

Alan David Moncreif-Wright was one of the staff members. He was a prolific offender, who had been caught abusing children in Hamilton but he was allowed to leave that institution and get a job at Epuni. Moncreif-Wright was a House Master – roughly the equivalent of a guard, a prison officer. He slept on site. The House Masters were all powerful. They had easy access to children. We had to obey them – if we didn’t we were disciplined.

I remember the first time Mr Moncreif-Wright abused me, he found a reason to send me to my room. Once in the room he came in and he sexually abused me. There was no escape. I was trapped.

After nine months at Epuni, I was taken out of there and put into a Family Home in Titahi Bay, Porirua. I was there for about three years. A similar culture existed there, but not as bad. The first day I arrived I distinctly remember sitting in the lounge. Another boy wandered in and, without introducing himself, he just punched me fair in the face. I had just come from a pretty rugged environment and I retaliated, which got me into trouble. Later I said to the boy, “Why did you do that? I don’t know you at all – I have never done anything to you.” He said, “because the kingpin told me to do it”. Some of the kids that were at the Family Home had been in Epuni Boys’ Home, so it was violent.

The male guardian at the Family Home was violent towards the kids. He sexually abused the girls. It was another abusive environment which saw my behaviour and wellbeing deteriorate. I was given an ultimatum when I was expelled from Mana College that I could do three or four months in Epuni Boys’ Home and then be given ‘school dispensation’ to allow me to go to work, or I could go to Invercargill Borstal. Those were my two options. I chose the first one.

The second time I went to Epuni, it was for about three to four months. Moncreif-Wright wasn’t there the second time around and I distinctly remember my first day back asking if he was there. I will never forget the response: “No he’s not, but turn your lights out at night, you’ll have a better chance.” I knew exactly what that meant.

The culture was the same and so were some of the staff. I remember I was standing on the line with the other kids and a fight had broken out. One of the staff was almost salivating over it and he just turned around to me and said, “Oh Keith, these kids aren’t quite as tough as when you were here last time”. These two kids were trying to kill each other and he did nothing to try and stop them.

When I left Epuni the second time around, I found myself throwing parcels in a sack for the Post Office at not quite 15 years old. I was still a ward of the State. I was not in good shape. I hated the world. I had a destructive attitude which saw me get into trouble, linking up with another kid or two from Epuni Boys’ Home and getting a minor criminal record at a young age.

I had no education. I was abusing alcohol, drifting from job to job, from boarding house to boarding house, with no sense of what I should do with my life to try and improve things. Looking back on my time at Epuni, the only positive was leaving it.

Many decades later, I went to police and told them what Moncreif-Wright did to me. The reason I made a criminal complaint against Moncreif-Wright was because somebody else had complained. Police contacted me as a potential witness, and I told them what happened to me. It ended up with three of us being involved in a criminal case against Moncreif-Wright.

I remember the Judge saying to Moncreif-Wright, who was deciding whether to change his plea, “you’ve got exactly five minutes to show these people some compassion.” He went out with his lawyer and came back and pleaded guilty. That told me something about the way the Judge saw the case.

In 2011 Moncreif-Wright was convicted of eight sexual offences in the Wellington District Court, including six against me. It turned out that in 1972 Moncreif-Wright had been convicted of three charges of indecent assault on boys aged under 16, and two charges of attempted assault. In 1988, the High Court sentenced him to four years’ jail for serious sexual offences. I cannot give an exact number of people Moncreif-Wright offended against, but I am very confident that he was a prolific offender.

It is not possible in my mind that the other staff at Epuni were unaware of abuse by their fellow staff members. I never saw a staff member face any consequences for their actions on either of my two stints at Epuni. I believe they did not face any consequences because of an administration that either didn’t know how to deal with it or didn’t want to. Either way they were as complicit as the offender.

State care had a devastating effect on me in those formative years. The impact of that period has continued throughout my life. I always wanted to get justice and an explanation for what happened to me.

I have thought about what a better system might be. First of all, there needs to be culture change. There are a range of things and the important thing is that when a young person goes into care, they are treated with dignity. Their needs may be different from others – it is about that person’s future. Investing at that level in those formative years is where you avoid having inter-generational prison populations, the continued growth of the gangs and all those negative outcomes.

Until it changes and the investment is made for young people, you are going to get the outcomes that happen here, which we all pay a price for. A massive impact on this country because we get it so wrong in those formative years.

Source

Witness Statement, Keith Wiffin (29 October 2019).