Survivor experience: Hēmi Hema Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

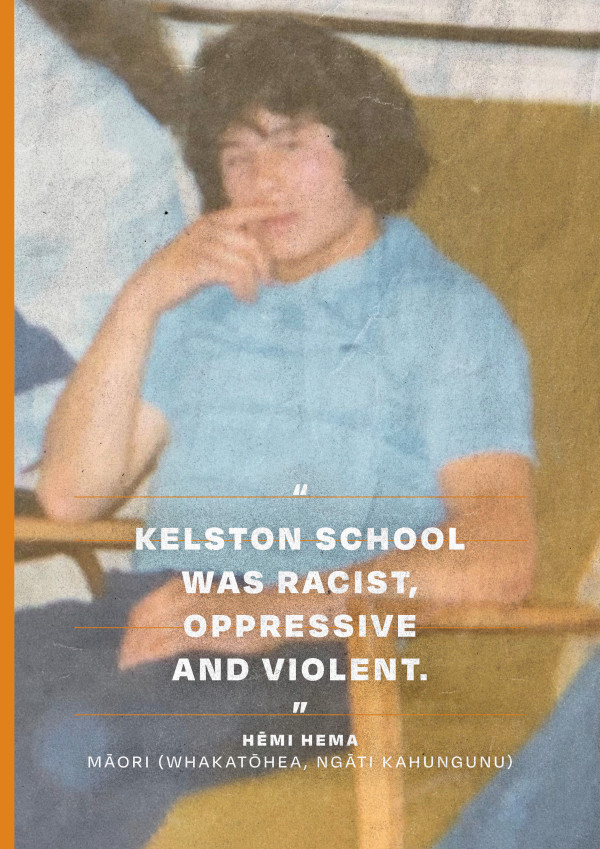

Name Hēmi Hema

Hometown Ōtautahi Christchurch

Age when entered care 5 years old

Year of birth 1970

Time in care 1975–1987

Type of care facility Schools for the Deaf – Van Asch College in Ōtautahi Christchurch, Kelston School for the Deaf in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

Ethnicity Māori (Whakatōhea, Ngāti Kahungunu)

Whānau background Hēmi is the only child of both his biological parents; his father had other children. He grew up with one sister, who is the daughter of his mother’s sister. She was whāngai into his whānau so they grew up as siblings.

Current Hēmi has been strongly involved with the Deaf community. He is president of Tū Tāngata Turi, a registered charitable entity for Māori Deaf. In 2012 he received a Queen’s Service Medal for his services to the tāngata Turi Māori community.

My mum had measles while she was pregnant with me and I was born Deaf. I went to Van Asch in 1975, at 5 years old, as a day student for a few months, then as a residential student. On weekends I stayed with my aunty.

I didn’t like being at boarding school. It was very isolating and I didn't like the staff. It was very strict, there were specific times when you had to eat dinner, and if you didn't like the kai you were sent straight to bed.

At Van Asch I recall being taught Total Communication and not New Zealand Sign Language. English was the big focus, but we developed our signing outside of the classroom with other Deaf kids in the playground. The other classes, like science and maths, were quite visual which was good. Total Communication didn't have that, so it was pretty pointless.

The teachers were all hearing Pākehā – there were no Deaf or Māori teachers. While I was there, about half the students were Māori but we didn’t learn anything about te ao Māori.

My family moved to Ōpōtiki and I went to primary school there but I was the only Deaf person and it was hard to learn. I was sent to Kelston, but I desperately wanted to go home. I felt very disconnected from my whānau, in a new place where I didn’t know anyone. A teacher saw me crying and they hit me with a wooden ruler. I was about 10 years old and this was my first experience of my new school.

I was at Kelston almost six years. The staff were all hearing Pākehā. There was a focus on oralism – they tried to teach us to lipread and vocalise, but I didn’t understand. In speech therapy, the teachers would make me press on my throat to feel the vibrations. If I got it wrong, they’d say I wasn’t pressing on the right place. It made no sense to me because I couldn’t hear anything. There wasn’t any learning.

We were taught to lipread but it was a waste of time. We were taught the alphabet, how to pronounce the letters, but it was really hard to understand the teachers. If I asked other students for help, I’d use sign, but teachers would tell us off. We were just trying to learn but they didn’t understand Deaf culture – they thought we weren’t paying attention.

The staff at Kelston were very abusive and they did whatever they wanted – the violence happened all the time. If we were caught using sign we’d be smacked with a belt or a ruler. If we cried from being smacked, we’d be sent to sit in the corner, and often we’d be smacked again. Once, a staff member hit me on the head, slamming it against the floor until my skin broke. I had a black eye and was bleeding a lot. I had to have butterfly stitches.

There was a lot of racism at Van Asch and Kelston. The Māori and Pacific kids were put down and stereotyped, and we were punished more. I’ve talked to other Māori who were there and it’s all the same – their anger and hatred towards us.

It wasn’t just the staff. The senior students would beat us up and sometimes sexually abuse the younger students. There were no staff around to stop this happening. When I had just arrived at Kelston, the older boys tried to intimidate me into doing sexual things with them. It was traumatic.

From when I was 13, a male staff member would have sex with me in my room at night, and he was abusing other boys as well.

I didn't tell the staff, I wasn't confident enough. This kind of abuse was very common at Kelston. There were others who abused me – I don’t know where they learnt this behaviour from, but I think maybe it happened to them.

Once, I got quite aggressive in response to all the fighting and violence, and I got my hands on a knife. I was about 14 or 15 years old. The staff called the NZ Police and I was taken away to a boys’ home, which felt like a prison. I was the only Deaf boy there and I couldn’t communicate with anyone. I had to go to court, and I just wanted to go home – I was tired, the staff were abusive and I was worn out from all of it. I was let off with a warning.

When I returned to Kelston I was kept separate from other students for two days. My mum came to Kelston and met with the principal, who said I was a safety risk. Eventually I went back but I kept getting into trouble. The staff were oppressive, and I was permanently kicked out when I was about 16 or 17.

My dad took me to Deaf Club when I was about 19 years old. When I got there, people were signing, there were even Deaf sports. It was lovely. I joined the Deaf rugby team, and I got involved in the Deaf community in every way I could, finding my own mana.

When I was 26, I was doing a disabilities studies course at the polytechnic in Ōtautahi and I went back to Van Asch to observe for a 12-week period. I sat in on classes, and even though many years had passed, a lot of the same problems were still happening. I often swapped with the teacher and helped out – just being able to have relevant communication as Māori Deaf with the kids in class made them so much more responsive.

Hearing teachers who don't know how to sign don’t understand this.

We need better protection of our tamariki Turi in schools. When I visit Van Asch, I am careful to keep my role professional. We need to make sure our tamariki are safe.[43]

“At both Van Asch and Kelston, the Māori and Pacific Island kids were put down and stereotyped, mainly by the staff and teachers. We were considered naughty kids and the pākehā were the well-behaved kids. We would do silly little things, that all kids do, but the punishment was full on ... ”

Footnotes

[43] Witness statement of Hēmi Hema (21 November 2022).