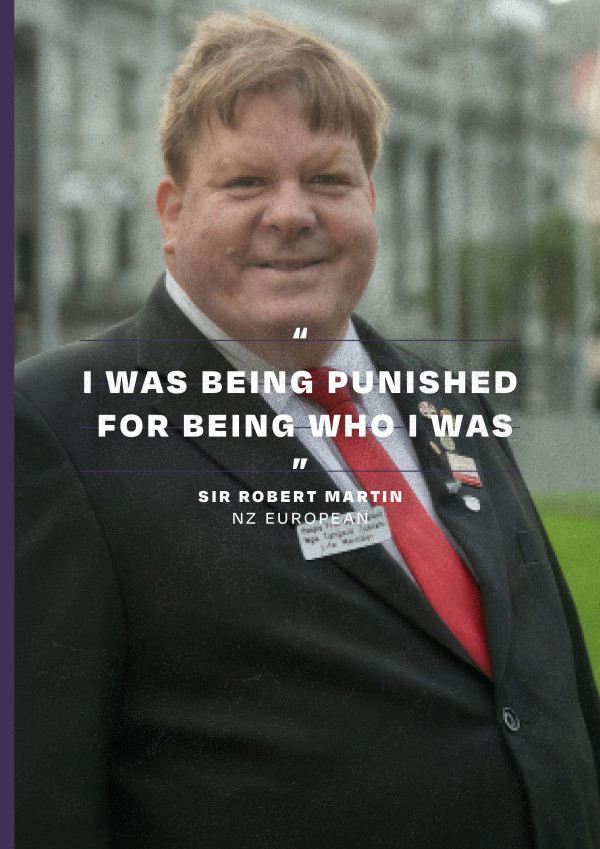

Survivor experience: Sir Robert Martin Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Name Sir Robert Martin

Age when entered care 18 months old, 9 years old

Year of birth 1957

Type of care facility Disability facility – the Kimberley Centre in Taitoko Levin, Campbell Park School in Waitaki Valley; psychiatric hospital – Lake Alice Child and Adolescent Unit in Rangitikei; foster homes

Ethnicity New Zealand European

Whānau background Sir Martin had a sister.

Currently Sir Martin passed away on 30 April 2024 and is survived by his wife. He had enjoyed a life packed full of books, music and sports once leaving the Kimberley Centre.

I’m a person first, disability second.

When I was born, the doctor damaged my brain during birth with forceps. My mother was told to send me away and forget about me, so I went to the Kimberley Centre, aged 18 months. Just because I was born with a disability. I was being punished just for being who I was.

I lost my family and was locked away from the community. I missed my family and cried for them and wanted them to take me home. But they didn’t come. So in the end I gave up crying for them.

It was lonely at the Kimberley Centre – there were hundreds of people around me, but as a little boy I didn’t know another human being. Not properly. As a toddler, I was fed and taken care of, but there were so many of us, we were just a number. I didn’t experience what other kids did. I didn’t go to birthday parties or feed the ducks or visit the zoo.

Institutions are places of neglect and abuse, where people are denied their human rights and basically denied a proper life. The right to education and the right to participate, the right to live free of violence, the right to life – these things are all at risk in an institution.

I went back to my family when I was 7 years old but my parents weren’t given any support or counselling and things just didn’t work out so I was made a ward of the State. I was 9 years old when I went back to the Kimberley Centre. I was now in a different ward, where the conditions were horrible – there were 40 kids in a dormitory. We had to share a pool of clothes and grab what we could. We never had our own underwear. There was no privacy and there was nothing to do. We were colour coded in groups and had labels and categories. We weren’t treated as individuals, and we were neglected. Punishment was severe and out of proportion to the behaviour.

At the Kimberley Centre I experienced abuse and I witnessed abuse. It was there that I was first sexually abused by a male nurse. I was so young I didn’t know what was happening. It should never have been allowed to happen. I learned not to trust people, just to try and survive as best I could. I became defensive and on guard all the time, just to keep away from violence and abuse.

If you were taken to Villa 5 at the Kimberley Centre, you knew you were in real trouble. The staff there were just evil. I saw this naked boy who had had an accident being hosed down by the staff using a fire hydrant hose. He would try to stand up and be knocked over again. I have seen many terrible things, but what I saw that day has stayed with me and still frightens me. It was a warning – if you misbehave, this will happen to you.

At one stage when I was in the Kimberley Centre, they gave me some medication that wasn’t ever meant for me. Whatever it was, it had a terrible effect on me and made me lean on my side. The effects lasted for a very long time. I was sent home and my family thought I was playing up so I got in trouble, but it was the medication. I should never have had to endure that.

When you’re shut away from the world, you’re not treated as a real person with a life that actually matters. People who have power over other people are easily corrupted, and behind closed doors, the human rights of others are often violated. This should not be allowed, but it was allowed.

At the Kimberley Centre, I personally had nothing and no one. I learnt that I was a nobody and my life didn't really matter. Children raised in institutions learn that good times don’t last, and people come and go. The result of this is very negative. We struggle with how to relate to people, we are always different and somehow catching up.

When I was released from the institutions at age 15, I had to learn to live and to survive all over again. This is very hard to do. I didn’t know lots of things other New Zealanders did. It was like I wasn’t even a citizen. I didn’t know about the All Blacks. I had never heard any of the radical music of the 60s. I didn’t know about the Vietnam War. These things everyone else knew about – it was like I was brought up on a different planet with different rules.

I remember the Springbok tour of New Zealand in 1981. The protests about rights and freedom for people in South Africa. I remember thinking, what about the rights and freedoms of all the people in New Zealand locked away in institutions? I remember feeling like I hardly had any human rights. Nobody was marching for me, or for anyone else with a disability.

I since have fought for the rights of people with learning disabilities and closure of institutions in Aotearoa New Zealand and around the world. I was elected to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2016. I was the first person in the world with a learning disability to be elected to a United Nations Committee. I was knighted for services to people with learning disabilities in 2020.

I now live a proper life but I could have had this as a child. Children are innocent and it is too risky to leave it to the State to look after them. They need to be part of a family, they need love, opportunities and individual care.

I don’t want disabled children to have the same childhood I did. My hope is that there is an end to segregation, institutionalisation and discrimination, and that all the children of tomorrow grow up in caring, well-supported families, and that schools, communities and societies shift to be inclusive of all people.

Everyone has a right to a life instead of wasting away in institutions waiting to die.[194]

Footnotes

[194] Witness statement of Sir Robert Martin (17 October 2019)